FEATURE – Capitol Reef is a marvelous mash-up of the four other Utah national parks.

Like Zion, it’s got majestic monoliths such as its signature Capitol Dome and narrow canyons such as Capitol Gorge. Like Arches, it boasts a few erosion-carved holes in its rock, such as Cassidy Arch. It features some hueful hoodoos and spires that would feel right at home in Bryce Canyon, such as Chimney Rock. And like Canyonlands, it contains rugged dirt roads leading to stunning scenery in wide-open spaces, including the Notom-Bullfrog Road that runs parallel to the park’s famous Waterpocket Fold as well as Cathedral Valley in its northern quadrant.

It doesn’t get as much attention as the other members of “The Mighty Five.” It consistently ranks lowest in visitation among Utah’s national parks and isn’t on as many must-see lists.

Those who skip over it are missing out, but that makes it less crowded for those who do visit the park, which could have been known as Wayne Wonderland if some early local boosters would have had their way.

Brief geologic history

Capitol Reef is the park’s moniker due to its distinct geology. The word capitol refers to the plethora of Navajo Sandstone monoliths that resemble the domes of capitol buildings. The reef refers to the long rocky cliffs such as the Waterpocket Fold, which, like ocean reefs, are barriers to travel, the park geology website explains.

“The geologic story of Capitol Reef can be broken down into three steps, each of which occurred over millions of years of geologic time: deposition, uplift and erosion,” the park geology website says.

The deposition refers to the sedimentary strata deposited in the park, which started 270 million years ago when Capitol Reef was at or near sea level. These deposits make up what the park geology website calls a “geologic layer cake” in which the rocks to the west are older than the rocks to the east. Large-scale plate tectonic forces caused these sedimentary layers to uplift thousands of vertical feet.

The Waterpocket Fold, which is a nearly 100-mile long warp in the Earth’s crust “is a classic monocline, a ‘step-up’ in the rock layers,” the geology website explains. “It formed between 50 and 70 million years ago when a major mountain building event in western North America, the Laramide Orogeny, reactivated an ancient buried fault in this region. Movement along the fault caused the west side to shift upwards relative to the east side.”

The Fold got its name from the “waterpockets” it contains, which are small, water-eroded depressions in its sandstone layers. It is that constant erosion that continues to carve the arches, monoliths, spires and canyons visitors see today.

Early natives and visitors

The Fremont culture, who inhabited the area from 300 to approximately 1300 A.D., were the Capitol Reef area’s first inhabitants. Named for the Fremont River which runs through the park, they lived in pit houses they dug into the ground and covered with brush roofs, as well as natural rock shelters.

According to anthropologists, these ancient peoples were hunter-gatherers who also grew corn, beans and squash along the river bottoms to supplement their diet, the Capitol Reef National Park website explains. They ground the corn into meal using a hand-held grinding stone on a stone surface. They ate native plants such as pinyon nuts, rice grass, bulbs and tubers and hunted local game including bighorn sheep, birds, deer, rabbits and various other rodents using atlatls, bows and arrows.

Petroglyphs, pictographs, pottery shards and basket remnants provide evidence of, and glimpses into, the life of these early inhabitants.

According to Capitol Reef’s administrative history, an 1854 exploring party led by John C. Fremont (for whom the river is named) were likely the first non-Indians to see a portion of today’s park.

“[Fremont’s] artist and daguerreotypist, Solomon N. Carvalho, wrote a very general account of their journey, and a couple of his sketches and a map seem to put them somewhere in the vicinity of Salvation Creek, just east and north of Cathedral Valley,” the administrative history surmised.

Fruita

There was once a town in what is now Capitol Reef and its origins are obscure, the Capitol Reef National Park website on Fruita’s history explains. Its first resident was most likely a squatter named Franklin Young, who came in 1879. Nels Johnson was the first landholder of record and others soon followed to a settlement at that time that went by the name of “Junction.”

Its location at the confluence of the Fremont River and Sulphur Creek meant that water to irrigate crops was readily available and the community which was built because of it could not have thrived without. The location proved favorable because the little town was often spared from the frequent flooding that happened to settlements farther down the river such as Aldrich, Caineville and Blue Valley.

Fruit, as seen by the orchards that survive today, became the town’s signature crop and as such, the community known as “the Eden of Wayne County” became Fruita in 1902. The town’s fruit growers traveled by wagon to larger towns such as Price and Richfield to take their crops to market. And travel wasn’t easy in the early days.

“In 1901, it took the (Latter-day Saint) Bishop of Torrey more than an hour and a half to travel the ten miles between Fruita and Torrey in the best weather,” the Fruita history web page explained. “If the road between Torrey and Fruita was difficult, the route between Fruita and Hanksville – 37 miles (59.5 km) east – was nearly impossible.”

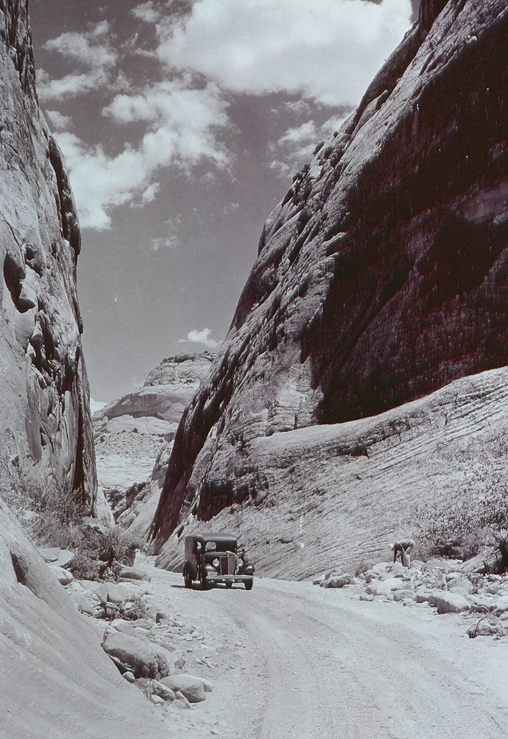

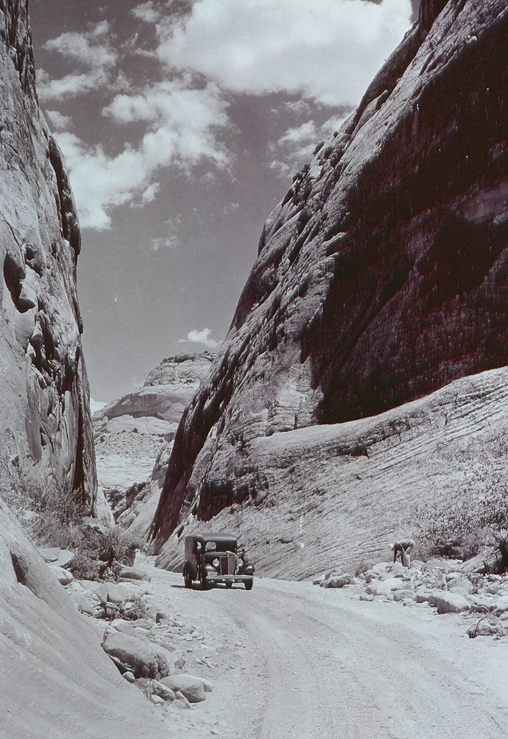

The area was one of the most isolated in the nation until the mid-20th century as community residents, in the late 19th century, took it upon themselves to build a narrow wagon track through Capitol Gorge that extended to Caineville and Hanksville. That crude roadway served the town until after World War II when better roads were built.

“Although it became widely known in south-central Utah for its orchards, Fruita residents also grew sorghum (for syrup and molasses), vegetables and alfalfa,” the Fruita history web page notes.

The one-room schoolhouse, located right off Highway 24 east of the visitor center, was the town’s social center. Fruita residents moved the school’s desks to give them space to hold dances and socials. The community also held church in the schoolhouse. When it came to leisure activities in the town, women enjoyed quilting and the men and boys were fond of baseball.

“Fruita was beautiful,” recounted Joyce Oldroyd Torgerson, a teacher who taught in the schoolhouse in the mid-1930s in an oral history available on the park website. “Across the dusty road, were row upon row of grapes, bordered by huge walnut trees. On moonlit nights, the majestic red cliffs seemed gentle and protective.”

Torgerson said that during the time she taught, the school was in need of repair and that textbooks were scarce. Classroom management, as it is for many of today’s teachers, was also a challenge.

“Like many rural children of the day, some of my students were pretty rough-and-tumble,” Torgerson explained. “The language I heard was too rugged for me, and I came down hard on that. Then there were the inevitable tricks. One morning I received a dead snake, coiled menacingly on my chair.”

As one can imagine would be the case in an isolated agricultural community, trade and barter were the primary means of acquiring goods and services as cash was scarce.

“Although some Fruita men worked on state roads, annual fruit sales remained the major source of cash income,” the history page says. “‘Putting up’ foods was not a hobby in Fruita; it was essential for survival through the winter.”

“The orchards, of course, took a lot of work, but we had beautiful fruit: apricots, peaches, pears, apples, plums and cherries,” remarked Dewey Gifford, who was a farmer and rancher from 1928-1969, in an oral history available on the Capitol Reef website. “We trucked a lot of it out of Fruita for cash sale or traded for grain with other farmers near Loa and Lyman.”

That barter system in place was actually advantageous during the Great Depression, shielding the community from the anguish of the drought on cash that swept the nation.

Fruita was a little behind the times when it came to farming practices and technology as the first tractor in the community was not purchased until after World War II. It was behind when it came to modern amenities as well.

“Until 1940, we used all teams and horse-drawn implements, mostly for growing and cutting alfalfa for animal feed,” Gifford explained. “For much of that time, we had no running water, electricity, or telephone.”

Fruita never incorporated and the population was always small, never exceeding 10 families according to the history page.

Families remained in Fruita even after Capitol Reef’s designation as a national monument in 1937, bucking the trend of private inholdings being immediately purchased by the government or turned over to it once the land in question came under National Park Service jurisdiction. After World War II, visitors began arriving to see the future park’s scenery in increasing numbers and better roads facilitated that. For instance, in 1940 the road from Torrey to Richfield was paved and that paved thoroughfare reached Fruita 12 years later.

As visitation increased, the NPS moved to purchase all private property in Fruita and most did sell willingly, seeing the writing on the wall. Many residential structures were razed. The home of the Gifford family and the barn on their property (known as Pendleton Barn for the first owner of the property) thankfully remain intact today. Dewey and Nell Gifford finally sold their property in 1969 and were the last Fruita residents to leave.

Even though most of the structures are gone, the orchards remain and dominate the landscape, deemed by the NPS as historically significant and worthy of preservation.

Photo courtesy of NPS, St. George News

Wayne Wonderland

Local entrepreneur Ephraim Pectol and his brother-in-law and Wayne High School Principal Joseph Hickman started working to protect the Capitol Reef area as early as 1914 with the dissemination of photos of a natural bridge later named in Hickman’s honor, the park administrative history noted. The duo wanted to share the natural and cultural wonders they revered with others and also hoped that the tourism generated from such a protected area would be a boon to the local economy. The two photographed and wrote about what they called “Wayne Wonderland” to promote the region at a statewide level, at first hoping for state park designation, the park’s “Park Founders” history page explains.

A state park movement was gaining steam in the mid-1920s and in July 1925, Utah Governor George Dern visited Wayne County with much fanfare, including a rodeo and a dance before a speech by the governor the next day. County residents hoped that their “Wayne Wonderland” would become the first state park, but it wasn’t to be. In his speech during his visit, Dern said: “the gorgeous and awe-inspiring scenery in Wayne County [was] destined to be made the first state park in accordance with the state park law added to [Utah’s] statutes during the last legislature.” However, as the administrative history reported, the event that included a speech by Governor Dern was organized “in hopes of encouraging future state and federal action, rather than to be an actual state park dedication.”

Unfortunately, the Wayne Wonderland movement lost its most staunch supporter, Joseph Hickman, less than a week after Governor Dern’s speech. Hickman, who had by then been elected a state legislator, drowned in Fish Lake. His death was a major blow to the movement, which wouldn’t pick up for another five years.

The National Park Service was not consulted about the possibility of a national park in Wayne County until 1931, when Zion Superintendent Thomas J. Allen, Jr. toured the area and concluded, according to the administrative history, that “the area was not ‘up to the standards of Zion,’ but worthy of official investigation.”

Allen recommended, with little enthusiasm, that Roger W. Toll, superintendent of Yellowstone National Park and head of official investigations into proposed National Park Service areas in the West, take a look at Capitol Reef. After his investigation in October 1932, Toll was as lukewarm about Capitol Reef coming under the jurisdiction of the NPS as Allen was, the administrative history concluded.

The movement started gaining steam again in 1933, when then Utah governor Henry Blood signed a resolution to the United States Congress detailing proposed boundaries for a park in Wayne County, detailing the local support behind it. Newly elected to the Utah State Legislature, Pectol wrote to National Park Service Director Horace Albright encouraging him to consider the establishment of a park or monument. Toll visited the area once again with a better report than the first one.

The next few years saw a back and forth between national and state officials on proposed boundaries and a name for the future monument. In 1935, Pectol and Toll decided on Capitol Reef as a name over “Wayne Wonderland” because the formerly popular moniker indicated a more locally focused area. After many years of promotion by local boosters, the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration set aside 37,711 acres as Capitol Reef National Monument, comprising a smaller area than the park encompasses today, spanning approximately two miles north of Highway 24 and ten miles south, just past Capitol Gorge, the administrative history explained.

Capitol Reef’s first custodian was a historical author most famous for his book “The Outlaw Trail: A History of Butch Cassidy and His Wild Bunch.” Charles Kelly became entranced with the canyons and deserts of Utah after moving to Salt Lake City in 1919. As he explored the area, his interest in its history grew. At the age of 52, he sold his printing business looking for a new career and he and his wife, Harriette, decided to buy land in Fruita and settle there, but the NPS was already in line to purchase the property. The Kellys decided to stay in Fruita, renting a house and staying there anyway.

Fortuitously, Kelly started rubbing shoulders with Zion Superintendent Paul Franke who, on a shoestring budget, was trying to find someone to watch over the new monument. In Kelly, Franke found his man.

“Franke saw Kelly as a man extremely well-qualified to look after the natural and prehistoric resources of Capitol Reef,” the administrative history said. “Kelly, for his part, was eager to join the National Park Service, and he found Capitol Reef to be a nice place to live and work. The deal was struck when Kelly agreed to take care of the monument for minimum pay and cheap rent.”

Kelly was to Capitol Reef what John Muir was to Yosemite: the most ardent of advocates. To him, it was “his” park. He was the only NPS presence in the monument throughout the 1940s and most of the 1950s. His job was a lonely one as he hardly ever saw staff from Zion or Bryce Canyon. Kelly did his best to fight off illegal grazing, vandalism, uranium mining, and anything else he considered disrespectful toward the land and his responsibility to protect it.

“His love of the landscape, and his determination to protect the monument’s resources helped build a solid National Park Service foundation when little money or outside assistance was available to do so,” the administrative history noted. He was “a man deeply committed to his job of protecting and developing Capitol Reef National Monument.”

Mission 66 and national park status

As part of the National Park Service’s Mission 66 program of the 1960s, which helped with capital improvements at the NPS’s 50th anniversary, Capitol Reef benefited with the construction of the Fruita Campground, a new visitor center and new staff rental housing.

Visitation climbed because of the development of paved roads to the area and the NPS moved to purchase all private inholdings.

On December 18, 1971, President Richard Nixon signed the legislation creating Capitol Reef National Park, which encapsulated 242,000 acres. On April 7, 1972, a formal dedication ceremony took place with Utah Governor Calvin Rampton, Senator Frank Moss and Representative K. Gunn McKay, among others.

Visiting Capitol Reef National Park

Capitol Reef is an almost three-and-a-half-hour drive northeast from St. George, taking northbound Interstate 15 to state Route 20, then U.S. Highway 89 to state Route 64 to Koosharem where one makes a right on a short highway that connects to eastbound state Route 24, which leads to the entrance of the park.

There is plenty to explore, from a boardwalk with outstanding views of petroglyphs left from its earliest human inhabitants to the remaining historic structures of Fruita, to its signature rock formations which include Chimney Rock, The Castle, Capitol Dome, Hickman Bridge and more. Hiking trails range from short jaunts to the 12-mile trip through Lower Spring Canyon accessed from the Chimney Rock Trailhead. Another fun activity is picking fruit in Fruita’s historic orchards while it’s in season.

At an elevation of approximately 5,600 feet, the summer heat isn’t too oppressive, but spring and fall are probably the best times to visit.

For more information about the park, visit its website.

Photo Gallery

These anthropomorph petroglyphs left by Capitol Reef's earliest human inhabitants are visible from a boardwalk easily accessible from State Highway 24, Capitol Reef National Park, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of NPS/Chris Roundtree, St. George News

This historic photo shows Fruita from above as it looked in 1931, Capitol Reef National Park, 1931 | Photo courtesy of NPS, St. George News

This historic photo shows a car passing through Capitol Gorge in the 1930s, Capitol Reef National Park, 1930s | Photo courtesy of NPS, St. George News

This historic photo shows the old entrance sign of Capitol Reef when it was a national monument, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of NPS, St. George News

The restored Fruita Schoolhouse is a fun historic stop right of Highway 24 just past the Visitor Center, Capitol Reef National Park, July 18, 2020 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The Gifford home is the only residence from Fruita's heyday still standing and is a great place to get a treat, Capitol Reef National Park, Sept. 3, 2016 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The Pendleton Barn, one of the last remnants of Fruita, makes the surrounding monoliths even more picturesque, Capitol Reef National Park, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of NPS/Byron Harward, St. George News

The author sits atop the current Capitol Reef National Park sign, Capitol Reef National Park, Sept 3, 2016 | Photo by Melissa Wadsworth, St. George News

Chimney Rock, Capitol Reef's striking spire near its west entrance, greets visitors along Highway 24, Capitol Reef National Park, July 18, 2020 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The Chimney Rock Trail provides stunning views of the spire from above, Capitol Reef National Park, July 18, 2020 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The Castle, one of Capitol Reef's most distinctive landmarks, sits atop its visitor center, Capitol Reef National Park, July 18, 2020 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The author and his family pose below Hickman Bridge, named for Joseph Hickman, an early booster of "Wayne Wonderland," Capitol Reef National Park, Sept. 3, 2016 | Photo courtesy of Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The drive along Highway 24 through Capitol Reef is a feast of rock spires and monoliths, Capitol Reef National Park, July 18, 2020 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Lower Spring Canyon is a lesser-traversed backcountry trail that starts at the Chimney Rock trailhead, Capitol Reef National Park, July 18, 2020 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

About the series “Days”

“Days” is a series of stories about people and places, industry and history in and surrounding the region of southwestern Utah.

“I write stories to help residents of southwestern Utah enjoy the region’s history as much as its scenery,” St. George News contributor Reuben Wadsworth said.

To keep up on Wadsworth’s adventures, “like” his author Facebook page or follow his Instagram account.

Wadsworth has also released a book compilation of many of the historical features written about Washington County as well as a second volume containing stories about other places in Southern Utah, Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada.

Read more: See all of the features in the “Days” series.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2022, all rights reserved.