FEATURE — The same year the United States was born, something else significant happened on the other side of the continent in an area that was not yet part of the country but would be in a little over a century’s time.

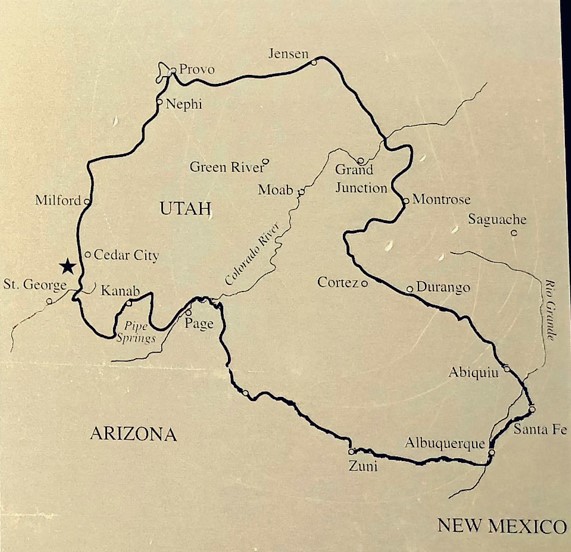

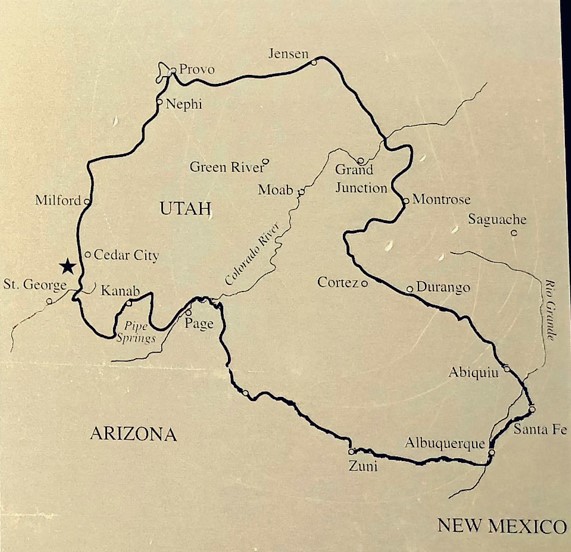

Two friars of the Franciscan order led an expedition across a largely unknown land – what would become New Mexico, Colorado, Utah and Arizona – on a quest to find a suitable trade route from Santa Fe to Monterey, California.

In fact, the party was originally supposed to depart on July 4, 1776, the very day of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, but got delayed because of Indian raids.

Many would argue that the climax of that epic journey occurred in Southwestern Utah.

Misconceptions and background

Fray Atanasio Domínguez, who was then head of the New Mexican missions, served as the leader of the expedition while Fray Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, a priest of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Zuni Pueblo, served as record keeper.

In the edition of the journal of the expedition translated by Fray Angelico Chavez and edited by Ted J. Warner published by the University of Utah Press in 1995, Warner dispels misconceptions about the roles of the two Franciscan fathers in his introduction to the volume. One of these misconceptions is that Escalante was the leader of the expedition since it has often been referred to as the “Escalante Expedition.”

In the introduction to his edition, Warner stated that his aim is to “accord to Father Domínguez a measure of much-belated credit for the heavy burden of responsibility he bore in relation to the expedition, but for which he has rarely been recognized. It was he who had the task of making the difficult decisions while on the trail, disciplining the members of the party, and bearing the responsibility for the safety of the men and the ultimate success of failure of the expedition.”

One of the reasons for this misconception, Warner explained, is that Escalante had already established himself as a keen observer.

“His letters and reports on frontier conditions were eagerly anticipated by higher authority,” Warner explained. “For his part, Father Domínguez was virtually an unknown and because of the complaints lodged against him by some of the New Mexico missionaries, his reputation was somewhat suspect.”

During a tour inspecting the New Mexican missions prior to the epic journey, Domínguez came down harshly in recommendations of discipline to several of them.

“His early 1776 inspection tour of the missions had been too honest and forthright, and to a certain degree, tactless,” Joseph Cerquone wrote in his book “In Behalf of the Light: The Domínguez and Escalante Expedition of 1776” published during the Bicentennial Year. “During his absence from Santa Fe, several missionaries had written letters to Franciscan authorities in Mexico complaining of his intolerance toward them.”

Thus, since Domínguez was somewhat despised and Escalante’s name was widely recognized, that’s why it became regarded as “his” expedition. Just the fact that there are several prominent place names in Utah that bear the name Escalante, such as the town of Escalante and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, gives an indication of Escalante’s popularity. The name Domínguez does not seem as significant when it comes to place names, however.

“The name ‘Domínguez Dome’ has been suggested for the place where Father Domínguez preached a sermon and exhorted the men on Oct. 11 to submit themselves wholly to the will of God and where they cast lots to determine whether to abandon the quest for Monterey or to press on,” Warner wrote. “In a low spot in the east rim of Paria Canyon, near the Crossing of the Fathers, there is also a ‘Domínguez Pass,’ named in honor of Domínguez.”

Warner explained that it is fitting Domínguez is being remembered with place names that relate to significant events that happened along the journey.

However, in fairness, Warner noted that it should be known as the “Domínguez-Escalante Expedition.”

Another point of clarification, Warner felt he needed to address, is Escalante’s name. His surname was Vélez and as such that’s the name by which he should be known. The name Escalante actually refers to his birthplace in Spain, but since the last name written is assumed to be the surname, he became known by it.

Another misconception is that no white man had ever been to the territory covered by the expedition. However, in his foreword to the Warner edition of the journal translation, Robert Himmerich pointed out that sections of the route the friars and their party took were already known.

“At least one member of the party had traveled to the Gunnison River with an expedition led by Juan Maria de Rivera in 1765, 11 years earlier, and as far as the Colorado River in 1775,” Himmerich wrote.

Nonetheless, Himmerich noted, the expedition was successful in providing a detailed inventory of undocumented land further inland for future explorers.

The journey through Utah: the expedition’s climax

Eight others joined the two friars when they departed Santa Fe on July 29, 1776. Along the way, various “mestizos” and Native Americans joined the expedition, most as guides for short stints, but some stayed on longer.

The two other members of the party of particular note were Don Bernardo Miera, a retired militia captain whose charge was to map the route, and Andrés Muñiz, an interpreter who spoke the Ute language and was the member of Rivera’s party in 1765 referenced earlier.

The expedition entered what is now Utah on September 11, 1776, going as far north as present-day Dinosaur National Monument. They then headed west through today’s Duchesne on their way to Utah Lake, which they reached on September 23.

Two major themes of the Escalante (Vélez) account are positive interactions with the Indians and the underlying motive of proselytizing to the native people. He made it clear throughout the journal that his group was on God’s errand.

One such Indian encounter he described on Sept. 30, when he mentioned that approximately 20 Indians arrived in their camp early in the morning, covered “with blankets of cottontail and jackrabbit furs.

“They stayed talking very happily with us until nine in the morning, as docile and agreeable as those before,” he noted.

Another encounter with a group of Indians a few days later (October 2) spoke to the missionary purpose of their journey:

“We announced the Gospel to them as well as the interpreter could manage it, explaining to them God’s oneness, the punishment He reserves for the wicked, the reward He gives to the righteous, and the necessity of holy baptism and of the knowledge and observance of divine law . . . We told them that if they wanted to attain the blessings proposed we would come back with more padres so that all could be instructed, as would those of the lake who were awaiting the friars, but that in such an event they were not to live scattered about as now but gathered together in towns.”

Despite this condescending call to try to organize the natives as the white man preferred, Escalante (Vélez) reported that the Indians invited them back, saying that the natives said “they would do whatsoever we taught them and ordered them to do.”

This is a great departure from the norm expected from the white man’s dealings with Indians.

Domínguez and Escalante were not typical explorers such as the “soldiers of the leather coats, bent on conquering native peoples,” Cerquone explained. “Rather, they sought and established a rapport with several tribes along the way, an accomplishment uncommon in the annals of the American West. They were men whose strong personal conviction, high enthusiasm and crusading purpose meshed well with a primitive country where life was, and in some parts still is, reduced to elementary struggle for survival.”

Evidence of Escalante’s role as an astute observer is in the same entry when he recounts the Indians inviting them back. He notices “some white and thin shells,” which he explained is evidence that there was once a much larger lake covering the area, obviously Lake Bonneville.

Between Oct. 5-7, they endured a snowstorm and frigid temperatures north of present-day Milford.

“We were in great distress, without firewood and extremely cold, for with so much snow and water the ground, which was soft here, was unfit for travel.”

This snowstorm, which made them feel an early winter was on the horizon, along with their realization of diminishing supplies, made the fathers rethink the continuation of their quest to Monterey. Several of the party, including Miera, the mapmaker, and Muñiz, the interpreter, still wanted to forge onward to Monterey. Miera thought their ultimate destination was only a week or two away. Both also had delusions of grandeur, “dreams of honors and profit from solely reaching Monterey and had imparted them to the rest by building castles in the air of the loftiest,” Escalante wrote of the occasion.

Between today’s Milford and Cedar City, the two friars grew extremely concerned about their situation and favored returning to Santa Fe despite the strong opinions by the others in their party to forge onward to Monterey.

To come to a final decision, they decided to leave it in God’s hands and cast lots, putting Monterey on one and “Cosnina”– their name for the Havasupai Indians – on the other. The one reading “Cosnina” came up, solidifying their favored decision to return to Santa Fe.

Just how they went about casting lots has been a significant discussion among historians. Warner noted in one of the footnotes in his edition some of the possibilities.

“They probably put the two names in a hat and drew one out,” Warner explained. “Some believe they wrote the names on a flat stick and tossed it in the air and followed the route which came out on top. Some cynics have suggested that the two padres, leaving nothing to chance, put two slips in the hat each with the name ‘Cosnina’ on it.”

The party headed south, passing by the Kolob Canyons section of Zion National Park without making mention of it in their journal and heading towards Black Ridge where they camped at “San Daniel” just off the I-15 Snowfield exit (Exit 33) on October 13 just after their Indian guides deserted them. They reached present-day Toquerville the next day and camped there on October 14. At this campsite, they were particularly impressed by the natives’ prowess in agriculture.

“On the brief bottoms and bank of the river, were three small maize fields with their well-dug irrigation ditches,” Escalante noted of the pleasing site. “The stalks of maize which they had harvested this year were still standing. We were particularly overjoyed by this, both on account of the hope it gave us of being able to provide ourselves with provisions farther ahead, and more importantly because it furnished evidence of these peoples’ practice of agriculture.”

The next day, October 15, they passed through present-day Hurricane. This was Escalante’s description of that small portion of the journey:

“We crossed El Rio del Pilar (Ash Creek) and El Sulfureo (Virgin River) near where they join, and going south we climbed a low mesa between outcroppings of black and shiny rock. After climbing it we got onto good open country and crossed a brief plain which has a chain of very tall mesas to the east, and to the west hills with sagebrush (what in Spain is heather) and red sand. On the plain we could have taken the edge of the cliffs and ended our day’s march on good and level land, but those who were going ahead changed course in order to follow some fresh tracks of Indians, and they took us over the hills and low sandy places mentioned, where our mounts became very much exhausted.”

What is known today as Sand Mountain was a major obstacle for them, but not more than the realization they had run out of provisions that very same day.

“Tonight our provisions ran out completely, with nothing left but two little slabs of chocolate for tomorrow,” Escalante wrote to end his entry for that day.

The next day, for lack of anything else to nourish them, they slaughtered one of their pack horses, an animal practically rendered obsolete by their lack of provisions for it to carry. “Tonight we were in direst need, with nothing by way of food, and so we decided to deprive a horse of its life so as not to forfeit our own,” he wrote that night.

Due to their undernourishment and the tough terrain, they traveled less than four miles that day.

They were forced to live off the land the rest of the trip, eating pinon nuts, cactus pears and small game as well as killing another pack horse to get by. By all indications, they never thought the horse meat was tasty. They just ate it to stave off hunger.

Their course east took them by what is now Kanab, across the Kaibab Plateau and down into House Rock Valley. They crossed the Colorado River via a raft they built out of logs from a tree they felled growing along the riverbank – a tree they were amazed to see. Their crossing point was not at today’s Lee’s Ferry, but further upstream at a place that became known as “Crossing of the Fathers” until it was submerged by the rising waters of Lake Powell. Today there is a Padre Bay in Lake Powell, named in their honor.

The fathers felt the river crossing was “a divine test of their courage and, perhaps, a chastisement for any wrongdoing by the expedition,” Cerquone wrote.

They forged onward, sometimes in bitter cold, finally returning to Santa Fe on January 2, 1777 after traveling over 1800 miles “and recording one of the greatest explorations in American history,” an informational plaque at the San Daniel campsite reads.

The epilogue

After his return, Domínguez found out he had been relieved of his duties as the head of all New Mexican missions due to his unpopularity.

“In later years, he was reassigned to various missions and isolated presidios throughout New Mexico and Northern Mexico,” Cerquone wrote. “When, in 1805, he died, at age 65, he was chaplain of the Presidio of Janos in Sonora.”

Upon his return, Escalante became a missionary friar at the Indian pueblo of San Idefonso and continued to write reports on what he considered unbecoming conduct of superiors, trying to encourage reform efforts. A kidney ailment hounded him the rest of his life. He died in April 1780 at the age of 30.

Miera died in 1785, “having lived a rich life of high adventure on the northern frontier of New Spain,” Cerquone wrote.

Almost nothing is known about what became of the others on the journey. They faded into obscurity.

Though considered a failure, information gleaned from the expedition aided later explorers. Miera’s maps were the first record information about the lands on the northwestern border of New Spain, Cerquone noted.

“Forty years later, other men would use this information to open the old Spanish Trail to California,” Cerquone wrote.

The what ifs

The colonization of Utah could have gone much differently had the expedition been true to one of the promises the friars made while on the journey.

Cedar City could have been known by the name Señor San José, the Virgin River by the moniker El Río del Sulfureo, and Toquerville could have been San Hugolino. These were just a few of the place names the Friar’s company named during their journey.

Today, the expedition can easily be regarded as a failure, because it did not reach its stated objective, Monterey. It could also be considered a failure because the Franciscans never returned to the Native Americans living near what is now Utah Lake, who impressed them tremendously, as originally promised. They had intentions of bringing the natives tools, equipment, seeds and cattle as well as teaching them the gospel, Warner explained.

Missionary efforts in New Mexico declined after their return. There simply wasn’t even enough men to occupy the already-open missions, leaving none to explore and establish new ones. Spain had also lost its interest in expansion.

“Had the Franciscans been able to return to Utah, missions, pueblos, and a presidio would no doubt have been located there,” Warner surmised. “Spanish customs, institutions, culture and religion would have become a settled and occupied part of the Spanish empire in the New World.”

Had that entrenchment of the Spanish occured, one could easily assume that leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints would not have considered Utah as a refuge from prolonged persecution in Illinois and Missouri.

“The failure of the Spaniards to capitalize on the information brought back by Fathers Domínguez and Escalante about central Utah was perhaps the most significant long-range result of the expedition,” Warner concluded in the introduction to his edition of the translated journals.

Other more grandiose and celebrated expeditions thought they were a failure, too. For instance, Meriwether Lewis of the Lewis and Clark expedition felt like his journey with the Corps of Discovery was kind of a waste. He however, did not see the fruits of his labor during his lifetime because he died young. If he would have lived a longer life, he would have seen the positive implications his journey had on the future expansion of the West.

The expedition of Domínguez and Escalante was no different. It has had a far greater legacy than the two friars could ever have imagined in their lifetimes.

Visiting sites along the route

The bicentennial of the expedition in 1976 led to significant interest in the journey and became the impetus of extensive field work in an attempt to locate the trail as precisely as possible and actual campsites as well as the placement of numerous markers along the trail still seen today and some interpretation of what happened at the precise site of the marker through plaques placed on or near each marker.

The most prominent and easily accessible Bicentennial Domínguez and Escalante Marker sits right in front of the Hurricane Pioneer Museum. There are markers and interpretive plaques at the Casting of the Lots site (approximately halfway between Lund and Minersville), the San Daniel campsite (off Snowfield I-15 exit 33) and others. Finding these markers can be a scavenger hunt for those interested.

While visiting the markers and retracing the steps of the original expedition, one cannot help but wonder how it would have looked devoid of all modern improvements, from telephone lines to paved roads to the numerous buildings that dot the landscape. It surely would have been a sight to behold, but alas a sight no one will ever see again.

Click on photo to enlarge it, then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

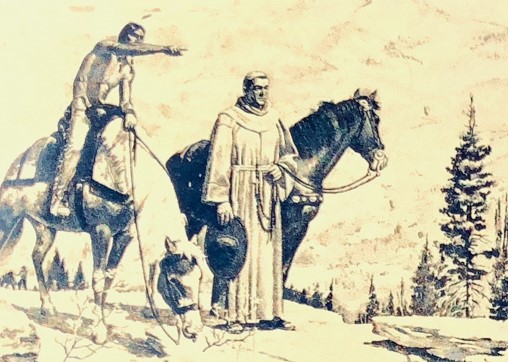

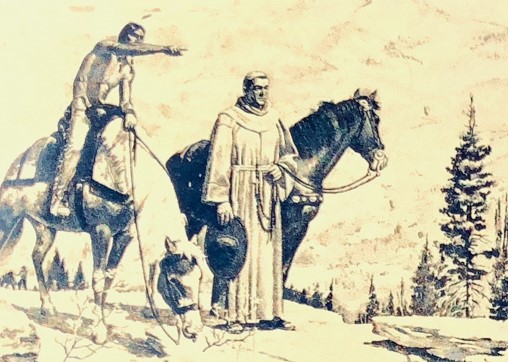

This artist's rendering of a Native American guiding the Domínguez and Escalante Expedition appears on the interpretive plaque at the San Daniel campsite near the Snowfield I-15 exit, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Mike Saemish, St. George News This map of the expedition's route appears on the interpretive plaque at the San Daniel campsite near the Snowfield I-15 exit, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Mike Saemish, St. George News A BLM post marks the location where the Domínguez and Escalante Expedition cast lots to decide whether to forge onward to Monterey or return to Santa Fe, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Mike Saemish, St. George News A wooden BLM sign marks a portion of the route taken by the Domínguez and Escalante Expedition west of Parowan, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Mike Saemish, St. George News This Domínguez and Escalante Expedition route marker stands on property in New Harmony, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Mike Saemish, St. George News A sign marks the spot where the Domínguez and Escalante Expedition camped at San Daniel, just off the Snowfield I-15 exit, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Mike Saemish, St. George News This Domínguez and Escalante Expedition route marker stands just above Pintura, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Mike Saemish, St. George News The most prominent and accessible Domínguez and Escalante Expedition marker in Washington County, placed during the journey's bicentennial in 1976, stands in front of the Hurricane Pioneer Museum in Hurricane, Utah, Feb. 10, 2020 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

About the series “Days”

“Days” is a series of stories about people and places, industry and history in and surrounding the region of southwestern Utah.

“I write stories to help residents of southwestern Utah enjoy the region’s history as much as its scenery,” St. George News contributor Reuben Wadsworth said.

To keep up on Wadsworth’s adventures, “like” his author Facebook page or follow his Instagram account.

Wadsworth has also released a book compilation of many of the historical features written about Washington County as well as a second volume containing stories about other places in Southern Utah, Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada.

See all of the features in the “Days” series.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2022, all rights reserved.