FEATURE — Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from across the world who live in far-flung areas have a history of making huge sacrifices to attend the temple. They save up for years for the expensive, long trip because of their firm belief in making covenants with God and in sealing themselves to the ones they love for eternity.

Those types of trips started along what became known as The Honeymoon Trail in the late 19th century when settlers in the LDS Arizona settlements made the journey to the St. George Temple through the barren desert in ox and horse-drawn wagons to ensure their relationships would last forever. These approximate six-week journeys (three weeks each way) from St. John’s, St. Joseph, Sunset and other Arizona towns along the Little Colorado River became foundational experiences for those who undertook them. They looked back at their traversings through the desert with fondness. One national park historian described even these journeys as the only vacations these individuals took as the rest of their lives were spent eking out a meager living in sometimes harsh conditions.

“Many of those who came considered their time on the trail and in the temple as the spiritual high points of their lives,” wrote Blaine M. Yorgason in his book “All That Was Promised: The St. George Temple and the Unfolding of the Restoration.”

“The trips to the St. George Temple arose from the deep faith that the Saints had in the eternal nature of marriage and the sealing power of the priesthood,” said H. Dean Garrett, assistant professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University in a July 1989 article in The Ensign. “The difficulty of getting to the temple created a memorable foundation for new marriages and set a pattern of sacrifice that did much to help the Saints settle the Arizona wilderness.”

The purpose

Other than a few days of marriage sealings performed in the Nauvoo Temple in early 1846 just before the exodus west, the Saints would not have an actual temple in which to perform marriages until the completion of the St. George Temple in 1877. Sealings for the living were performed in the interim in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City from 1855 to 1889.

Valerie P. Young’s master’s thesis to complete her graduate studies at Utah State University entitled “The ‘Honeymoon Trail: Link to Community and Sense of Place in the Little Colorado River Settlements of Arizona, 1877-1927” sheds a particularly interesting light on the journeys these settlers took to ensure their marriages would last forever.

Depending on the source, within a year to four years after the St. George Temple’s dedication, couples from Arizona’s Little Colorado settlements started making the trek over what was called the Mormon Wagon Road to St. George to be sealed for time and all eternity. Young said the first couples started along the trail in 1878, while other sources claim it was three years later.

“Telling stories about their wedding trips on the Mormon Wagon Road verified for the settlers the truth of the teachings about temple marriage,” Young wrote. “While many Latter-day Saints living in Utah also traveled to the St. George Temple, only the Arizona Saints made a tradition out of it, suggesting that the Arizona Saints needed to validate that they still belonged to the LDS community as a whole.”

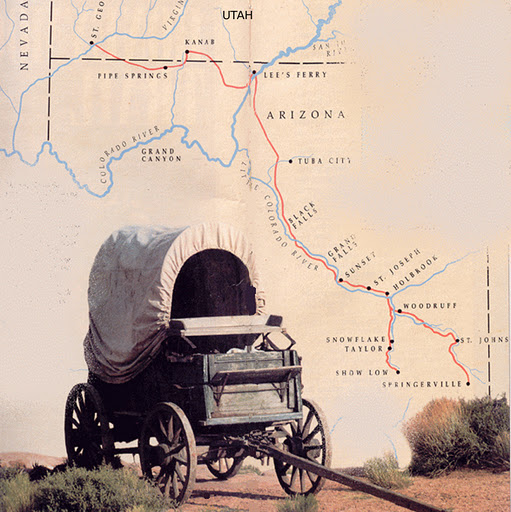

The Route

In the 19th century, anyone traveling to St. George from anywhere in Arizona had only one choice of a route: The Mormon Wagon Road, named, of course, because LDS settlers were the ones who blazed it and its most frequent travelers. There were no stage lines that ever connected any point in Arizona with Utah, Young reported, saying, “the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River gorge effectively cut the northwest corner of Arizona off from the rest of the state.”

According to Young, the route the honeymooners had to take was arduous, but it had water along the way, which was a critical factor in the days of wagon travel. Wherever the Saints who traveled to St. George were coming from, once they reached the Little Colorado near present-day Cameron, Arizona, their route was the same, Young explained.

From Cameron heading north, drivers on today’s U.S. Highway 89 basically follow the route of the Honeymoon Trail, which passed the Echo Cliffs and Bitter Springs then crossed the Colorado River at Lee’s Ferry, about a mile upstream from Navajo Bridge, where Alternate Highway 89 now crosses the Colorado River.

From there, Alternate Highway 89 leaves the old trail, which skirted the Vermilion Cliffs on its way to House Rock Springs, one of the main resting spots along the trail because of its good water, feed and fuel, Young noted. The spring and the whole valley bears the name of House Rock because between 1870 and 1880 when Indian missionary Jacob Hamblin used the trail about once a year he and his company took shelter in two large rocks that had fallen together. On one trip, an unidentified traveler inscribed in charcoal the words “Rock House Hotel.” Later travelers inverted the name and applied it to both the valley and spring.

Rocks along the trail became a sort-of register of the migration as travelers carved or wrote their names with axle grease on the rocks at resting stops such as the “Rock House Hotel.” One landmark along the route still to this day bears the name Signature Rock.

Alternate 89 crosses the Kaibab Plateau about 15 miles south of where the honeymooners would have crossed, Young wrote.

By taking Highway 389 from Fredonia, the modern traveler can continue a bit longer near the old route, passing what is now Pipe Spring National Monument, which in the honeymooners’ day was a tithing ranch, where in-kind tithing was collected and distributed. It was also home to a large cattle herd and as the name suggests, a source of water.

After Pipe Spring, the old Honeymoon Trail continues in a more westerly direction than the present-day highway towards Short Creek, then to Antelope Springs on top of Hurricane Hill. The home stretch took them down the hill to Fort Pearce and onto St. George.

Life on the Trail

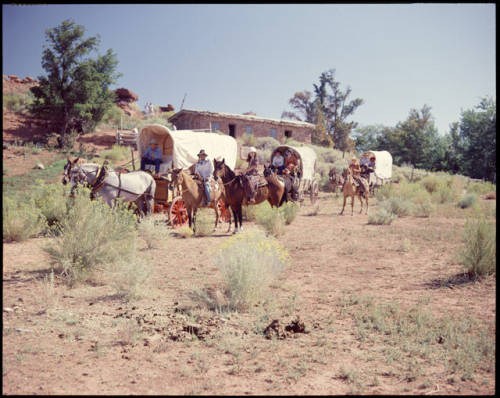

The earliest travelers along the trail often used the same wagons and teams of oxen they had used in their move to Arizona. Later travelers used mule- or horse-drawn wagons or even buggies.

Eventually, the preferred wagon for the trip became what could be described as a 19th-century version of today’s recreational vehicle. These wagons, which were known as “Prairie Pullmans” or “Sheep Camps,” were equipped with a cookstove, a kitchen cupboard, and a mattress, which Young noted made the trip more comfortable.

In his book, Yorgason detailed the trip of what he and other sources claim to be the first couples to make the trip, Alof Larson and his bride, May Hunt, who made the trip in October 1881 with Larson’s sister, Emma, and her future husband, Jesse N. Smith, who was the Snowflake Stake President at the time. Couples never traveled the trail alone. They always had chaperones in tow and some, who were married civilly long beforehand, brought their children along for the journey so the whole family could be sealed in the temple.

Of the Larson-Hunt-Smith trip, Yorgason related that the two women slept in the wagon and the two men “occupied the great outdoors,” a common practice for future travelers.

“A rollicking camp song was composed and sung often, everyone was in high spirits, the miles slipped by without incident or mishap – except that Miss Hunt developed a boil under her arm that Emma poulticed with a strip of bacon, the only thing available, and always she laughed when she applied it,” the Larson’s daughter, Louise Larson Comish wrote of her parents’ journey, as quoted by Yorgason.

As Comish related, evenings around the campfire visiting and singing together was one of the events that honeymooners looked forward to most along the trail. Charles Flake, one of the few men who kept a journal along the trail, noted that the men in the party he traveled with tried to beat each other at “telling big tales,” Young recounted in her book.

Young wrote that there was “a sort of unwritten ‘handbook’ to the trail developed, arising from collective experience with the Arizona landscape.” One of the strong suggestions of that “handbook” was to travel during the fall months because temperatures were pleasant and the rains from Arizona’s summer monsoon season had replenished the watering holes. While the temperature was tolerable in the spring, the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers could be raging torrents due to spring runoff, presenting major obstacles. Summer, of course, was too hot and meant that there might be a lack of water along the trail as well. Nearly no trips occurred during the summer.

Large spans of the route contained heavy sand, which taxed the energy of the teams pulling the wagons. But these resourceful travelers took advantage of the sand, Young explained, by burying caches of hay and grain for use on the return trip, which lightened the load and sometimes eliminated the need to buy feed in St. George before departing for home.

Since these marriage parties had already taken this route once when they traveled down to settle the area, they were familiar with the landscape.

“The accounts of the moves are filled with a sense of awe at the ruggedness of the terrain, and they describe in great detail their first encounter with the landscape,” Young explained. “For most honeymooners, the landscape had become so much a part of their subconsciousness by then that it became merely a backdrop for other memories of the trip.”

According to Garrett, the biggest problem in traveling the route was water. For instance, he wrote that water in the Little Colorado River was not fit to drink.

“As one traveler found, ‘The water in the river was very muddy; we filled a seven-gallon kettle to settle overnight and in the morning there was only an inch of clear water so we had to make the best of it.”

Finding forage for livestock was also a challenge at times, many sources detailing the Honeymoon Trail conclude.

Returning honeymooners recounted many positive experiences, but there were harrowing ones, too.

For instance, one female diarist told the story of encountering a large group of prairie wolves, who backed down and left when the men of the group started firing guns at them. The howling of the wounded wolves and the firing of the guns finally frightened them away. Another female diarist, Ida Udall, describes a time when a set of prospectors followed her party, making it nervous. Finally, the prospectors engaged the group in conversation and said they wanted to buy some grain.

“Their manner indicated that if we refused, they would take it anyway,” Udall wrote, as quoted by Young.

Under the circumstances, the party felt it prudent to sell the prospectors a few pounds of grain, afterwhich, the seemingly rough customers departed.

There are other tales of run-ins with Indians, one that is oft repeated is a group of Native Americans being relentless in wanting to buy one couple’s three-year-old blonde daughter and followed the party for a while but discontinued their pursuit at Buckskin Mountain. Another frequently recounted tale of an encounter with Indians is when 16-year-old Julia Ellsworth West was left alone one morning when her fiance went to look for horses when American Indians arrived asking for something to eat. West showed them the “almost empty lunch box, and after a while they decided to leave, much to her relief, she related, as quoted in Young’s thesis. It also reports there were isolated incidents of killings by Indians here and there in the area, which kept honeymooners a little on edge.

Young noted that these honeymooners wrote of concerns as well as pleasant experiences, but most of the descriptions of the trips were written years later, showing that, “time had caused the details of the journey to take a back seat to the reason for the trip.”

Stories related usually happened at specific landmarks along the trail. One of the landmarks that elicited the most stories and fear was Lee’s Ferry, specifically “Lee’s Backbone,” a formidable rock formation that proved to be an obstacle in the approach to the ferry on the Colorado River’s south bank. Young explained that if travelers reached the river during a low-water stage, “they could bypass the worst of the climb and go through a dugway that skirted around the south side of the Backbone.”

However, reaching the river during high water prevented the easier approach on the dugway and required going up and over a steep, jagged rock to reach the ferry crossing. Thankfully, the honeymooners traveled lighter than they did when they traversed the obstacle in their original move to settle the area, which made crossing the backbone a little easier.

In a letter to her parents one traveler along the route, Catharine Cottam Romney, called the Lee’s Backbone road the worst of the journey, saying that “there is one place where if a person went two feet out of the road, they would go down a precipice hundreds of feet.”

“We had to take our wagon apart to cross on the small boat,” West recounted about her party’s crossing at Lee’s Ferry. “We had a very narrow escape of being drowned.”

“Everyone who ever came over that piece of road had great cause for thankfulness they were not killed,” Garrett wrote.

Another traveler, Anna Maria Isaacson, who was driving a team of mules so her father could help with the cattle, wrote the following account, as quoted in Young’s thesis: “ … it was all I could do to hold onto those mules. Mother was afraid every minute I would tip over and be killed.”

One of the most-remembered tragedies along the trail during the peak travel along it is the death of May Whiting at House Rock Springs in 1882. She had been ill for some time and wanted to return to Utah to see her family but died along the trail before she reached her original home. Many later travelers mention her grave in their accounts.

Other than the accounts of the diarists, there are few accounts that actually describe the whole journey. To Young, much of what is known today of the honeymoon trail can be classified as “community authorship.”

“Each account echoes the others by emphasizing the purpose for the journey, as well as creating a sense of belonging to tradition,” she wrote.

After the settlers arrived in St. George and achieved the purpose for the journey, their temple sealing, some remained for a few weeks to visit friends and family members and rest, Garrett explained. Those who did have friends and family members in St. George usually lodged with them. Those who did not have such connections occupied the extra rooms of St. George residents’ homes. For example, St. George resident Flora Wooley said her spare bedroom was “always occupied” during the peak period of honeymooner travel.

The end of an era and the nostalgic name

When the Salt Lake Temple was completed in 1893, travel along the Mormon Wagon Road dropped dramatically as LDS couples in the Arizona settlements began taking the train from Holbrook, Arizona to Northern Utah by way of Los Angeles. The Salt Lake Temple, because of the ease of access to it via railroad, became the preferred location for farther-flung young LDS settlers to eternalize their unions.

“A 1913 guidebook to Arizona, published by the Arizona Good Roads Association, shows no roads north of the Grand Canyon, indicating that use of the Mormon Wagon Road by that time had dwindled to almost nothing,” Young wrote.

Between 1878 and 1895, the peak period of journeys to the St. George Temple by Arizona settlers, no one ever referred to the trail by its currently accepted name. Many believe that Will C. Barnes coined the name. Barnes, a retired army officer who was not LDS, bought a ranch near one of the Little Colorado settlements in 1883 and extended his hospitality to many wedding parties traveling to St. George. Barnes wrote an article in the December 1934 issue of “Arizona Highways” magazine about his experiences with the couples over the years, entitling the story, “The Honeymoon Trail.” Barnes’ inspiration for writing the story was a newspaper article he read about the new road between Flagstaff, Arizona and Kanab, Utah that called the route the “Old Honeymoon Highway,” Young explained, which indicates that the name was already part of the oral tradition.

In her research for her thesis, Young polled members of chapters of the Sons of Utah Pioneers in Arizona and began to realize that to the descendants of those who traveled the route, the Honeymoon Trail is more than just the period when wedding parties traveled in wagons. To them, it also included the later train trips to Salt Lake City and the later trips to the Mesa, Arizona, Temple after it was dedicated in October 1927.

“It became more and more clear to me during my fieldwork that when speaking of the Honeymoon Trail, most people are referring to an event, rather than an actual geographic location of the old trail,” Young concluded. “The emphasis on the purpose for the journey rather than the location of the trail, I believe, stems from a desire to be one of the heirs of tradition.”

Since Barnes’s 1934 article, “Arizona Highways” has published other pieces about the Honeymoon Trail, most of them written by non-LDS authors and according to Young, they “are all based upon the tradition of the trail rather than historical research, which emphasizes that a sense of belonging is one of the main factors prompting continued interest in the tradition.”

Descendants of those who traveled the trail take pride in the experiences of their ancestors.

“The Honeymoon Trail has become a uniquely Arizona LDS tradition that ties expressions of religious beliefs to a place,” Young wrote. “The intangible shared sense of importance of temple marriage combined with the tangible shared experience of trail travel to the temple, developed into the tradition of the Honeymoon Trail. It is a tradition that transcends time and binds the current generation to their ancestors and to the history of the Little Colorado settlements.”

“The Little Colorado settlers attached a great sense of importance to belonging to the Honeymoon Trail tradition: it gave them pioneer status – the ultimate pedigree in LDS culture,” Young explained.

Interpretation of the honeymoon trail at Pipe Spring

As a major stop along the Honeymoon Trail, Pipe Spring National Monument interprets life along the old wagon road for today’s visitors.

“Lots of honeymooners more than likely camped in their wagons near the fort and we do have references of honeymooners staying in the fort itself in the upper story of the south building next to the telegraph office, said Sara Black, Education Technician at Pipe Spring. “You can see the old wagon road from the West Cabin. It is very clear and obvious. From the ridge trail at the monument, you can see quite a bit of the trail as well.”

The name alone regularly intrigues visitors. The “entry point” for talking about the Honeymoon Trail with visitors is talking about the Old Spanish Trail, which the Mormon Wagon Road followed in some sections, Black explained. Pipe Spring rangers describe the stops along the route and the average amount of time it took to make the trip one way, which was three weeks. A major focus is on the reason for the trip – temple marriage – which Black said helps visitors understand its cultural and religious significance.

At times, Pipe Spring rangers will tell stories of specific honeymooners, which leads to talks about polygamy. Interpretation varies depending on the ranger. Black said rangers lead away from the negative associations of polygamy, depicting LDS polygamous women as fairly independent. They do speak of the tensions surrounding it, and mention that some of the honeymooners entered polygamous marriages and after the weddings in the St. George Temple, went their separate ways and met up months later to avoid capture by federal marshals.

Some visitors recognize Pipe Spring as a stop on the Honeymoon Trail right away and connect it to their family stories. When visitors push the buttons on the signage to hear some of the stories of the Honeymoon Trail, some of the voices of locals telling the stories, which provides another connection to the past, Black explained.

On the surface, Pipe Spring might look inconsequential as such a small monument, Black said, but many visitors find in it a personal connection to the past in the epic journeys of faith of those who had a more difficult life than most visitors today can imagine.

Visiting stops along the Honeymoon Trail

The Days Series has covered the histories of several stops along the Honeymoon Trail. Please view the stories on Lee’s Ferry, Pipe Spring and Fort Pearce to learn more.

Click on photo to enlarge it, then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

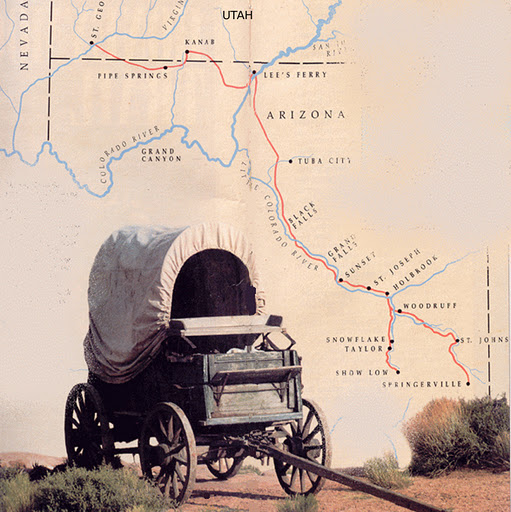

This map graphic shows the route of the Honeymoon Trail to the St. George Temple from the LDS settlements along the Little Colorado River in Northern Arizona | Map graphic courtesy of the Washington County Historical Society, St. George News This historic photo shows a group of people recreating what a travel party might have looked like during the time of the Honeymoon Trail at Pipe Spring National Monument, Arizona, 1950-1970 | Photo courtesy of the Norther Arizona University Cline Library Special Collections, St. George News The St. George Temple was the ultimate destination of couples traveling the Honeymoon Trail, St. George, Utah, Oct. 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News Lee's Ferry in Northern Arizona, was the spot where all of the travelers along the Honeymoon Trail crossed the Colorado River, Lee's Ferry, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News A wagon on display at the Lonely Dell Ranch near Lee's Ferry, Arizona, which is the place where all of the honeymooners crossed the Colorado River, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News A wagon and old cabin sit at Lonely Dell Ranch, near Lee's Ferry, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News The Honeymoon Trail skirted the Vermilion Cliffs, now a national monument, on its way through House Rock Valley, Cliff Dwellers, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News The Honeymoon Trail traversed House Rock Valley, as seen from a viewpoint along Alternate Highway 91 as it descents from the Kaibab Plateau, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News Winsor Castle, its surrounding buildings and spring were a major stop along the Honeymoon Trail, Pipe Spring National Monument, Arizona, May 5, 2010 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News A covered wagon on display near Winsor Castle at Pipe Spring National Monument, Arizona, May 5, 2010 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

About the series “Days”

“Days” is a series of stories about people and places, industry and history in and surrounding the region of southwestern Utah.

“I write stories to help residents of southwestern Utah enjoy the region’s history as much as its scenery,” St. George News contributor Reuben Wadsworth said.

To keep up on Wadsworth’s adventures, “like” his author Facebook page or follow his Instagram account.

Wadsworth has also released a book compilation of many of the historical features written about Washington County as well as a second volume containing stories about other places in Southern Utah, Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada.

See all of the features in the “Days” series.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2022, all rights reserved.