FEATURE — A landscape highly regarded by photographers today was not held in such high esteem by mining operations of the late 19th century. What is now an Instagrammer’s dream was a dumping ground of yesteryear.

Named for stately structures a continent away, Cathedral Gorge State Park is a remarkable pocket of awe-inspiring scenery in the midst of run-of-the-mill terrain. It is a truly unrivaled geologic spectacle that has become much more popular in the last decade with the emergence of social media.

The nearly 2,000-acre park was once home to Fremont, Anasazi and Southern Paiutes. White settlers arrived in the late 19th century.

Today’s visitor center sits on the former site of Bullionville, which was a location for smelting ore from Pioche because of its nearby water source, Nevada State Park Eastern Region Interpreter Dawn Andone said. By 1875, the town grew to 500 people and boasted five mills and the first iron foundry in Eastern Nevada, a historical marker near the site says. That same year, however, a water works was constructed in Pioche that eventually led to the relocation of the mills.

“Although a plant was erected here in 1880 to work the tailings deposited by the former mills, this failed to prevent the decline of Bullionville,” the historical marker reads.

In the 1890s, Mrs. Earl Godbe, the wife of a mining foreman and resident of Bullionville, was one of the first visitors to appreciate the future park’s unique, sculpted landscape. While riding horseback into the park, Godbe admired the eroded siltstone spires, which reminded her of European cathedrals, prompting her to suggest the name Cathedral Gulch for the area (at first it was known as Panaca Gulch), a historical marker at Miller Point explains.

The name later became Cathedral Gorge, which many felt had a better ring to it. Andone said that she swears changing the name was a marketing ploy for the state park because, “Who wants to go to a gulch?” she jokingly remarked.

Nearby mines saw no economic use for what became Cathedral Gorge and basically used it as a garbage dump, Andone said.

“In 1911, Nephi and Elbert Edwards, two teenage boys from Panaca, began exploring the nooks and crannies of Cathedral Gorge,” an interpretive sign at Miller Point explains. “They and their brothers built a series of ladders through cave-like crevices and crawlways.”

More curious visitors who thoroughly explore those “nooks and crannies” today might also find some ropes to help them. Andone said park staff has taken down some ropes, but one in particular in an opening reached by “the rabbit hole” somehow keeps finding its way back up.

“We don’t encourage people to climb that rope,” Andone said. “Visitors can use it at their own risk.”

During the 1920s, Cathedral Gorge provided the background for open-air plays and annual Easter ceremonies.

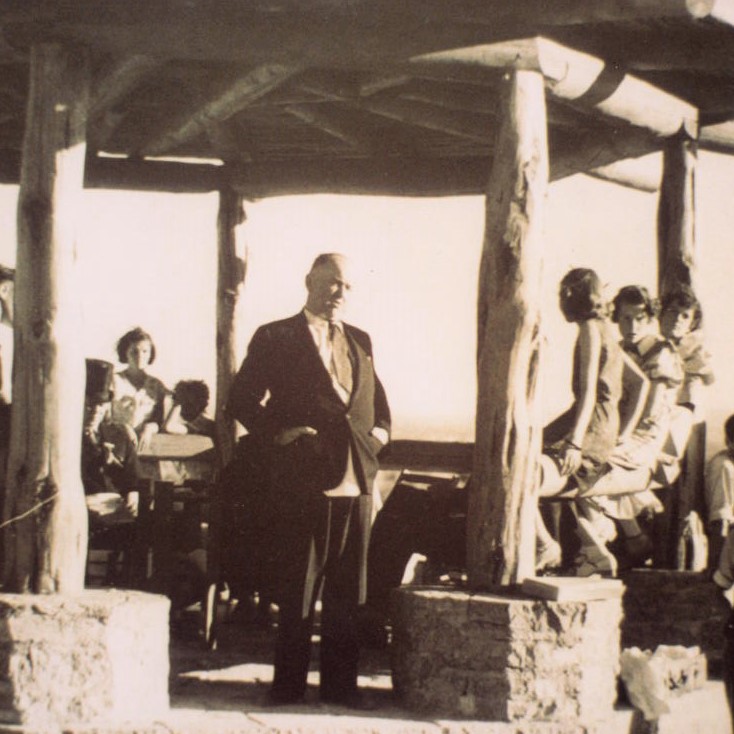

In the early 1920s, the Edwards families led the movement to preserve and protect the Gorge and found a willing listening ear in Governor James Scrugham, who was a huge proponent of state parks. Scrugham set aside the land for preservation in 1924 and in 1935, it officially became a state park under the watch of a new governor, Richard Kirman. However, Scrugham spoke at the dedication ceremony as a U.S. Congressman.

To this day, Andone admits there is a little bit of a rivalry between Valley of Fire and Cathedral Gorge as to which park was designated first. Valley of Fire feels it was first because its dedication ceremony came first, Andone said. Kershaw-Ryan and Beaver Dam state parks became the other two foundational parks of the Nevada State Park System. Three out of the four of the first Nevada State parks are in Lincoln County, Andone said (Valley of Fire being the lone one in Clark County).

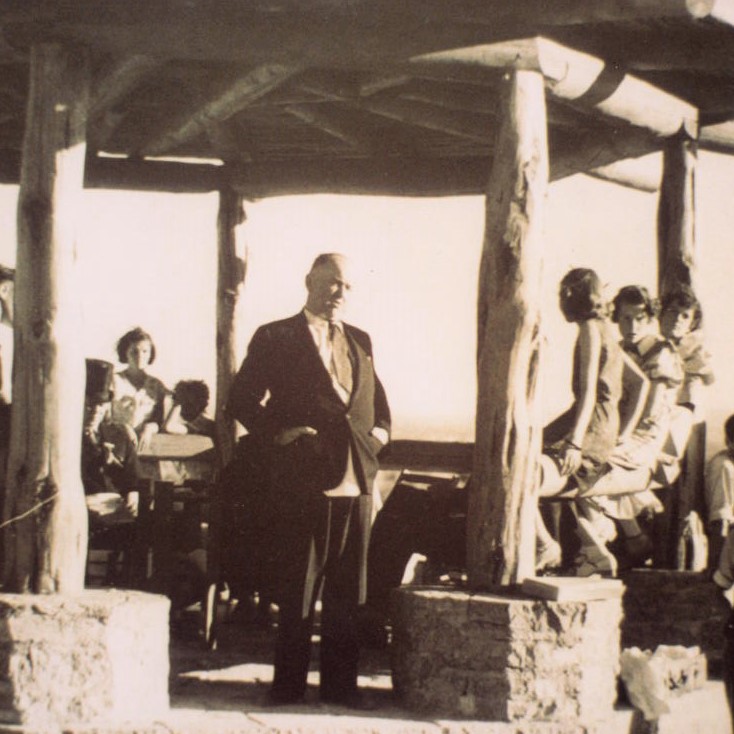

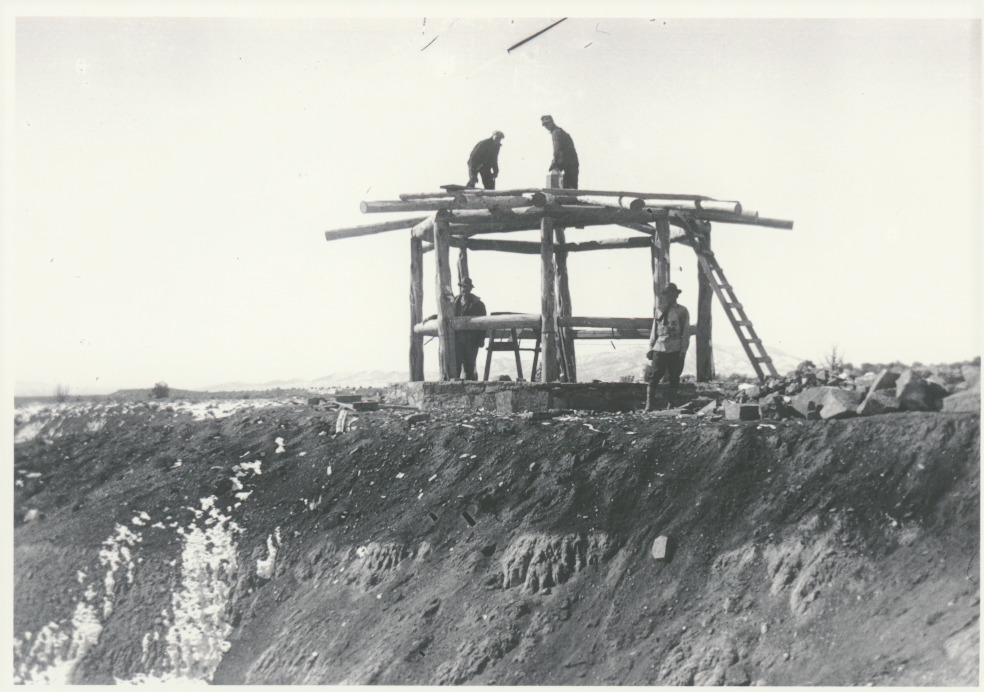

In 1934, members of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) arrived to start building facilities for the park, including picnic pavilions, a bathroom, a water tower and a bowery fashioned from Juniper logs at Miller Point, which was named for the head of CCC operations in the area at the time, Col. Thomas Miller. It was at that bowery at Miller Point where the official dedication ceremony of the park took place. The picnic facilities are still in use today, but the water tower and bathroom are not.

The CCC worked in Cathedral Gorge between 1934 and 1935. Another CCC group came back in the early 1940s, but mostly worked on flood control, Andone said. The remaining CCC-era facilities in the park are some of the only remaining CCC-built structures in the area as many other such facilities were destroyed over time by weathering.

“The fact that the buildings are still standing is a testament to how well built they are,” Andone said.

The old water tower is definitely the most prominent of the CCC-era buildings. None of the structures are on the National Register of Historic Places but are protected because they lie within the boundaries of a state park, Andone explained.

Some of today’s visitors mention that their grandparents met because of the Cathedral Gorge CCC camp, Andone said. The history of the CCC is replete with CCC boys from other places marrying local girls from the places they are assigned to labor.

Geologic history

The question for most visitors upon seeing the park’s landscape is: “How was all of this formed?”

The singular landscape visitors see in the park is the result of over tens of millions of years of geologic processes that included explosive volcanic activity and submersion under a lake. Grand volcanic eruptions from the Caliente Caldera Complex, which lies south of the park, deposited layers of ash hundreds of feet thick. Approximately five million years ago, these eruptions ceased, after which block faulting – a fracture in the bedrock that allows two sides to move opposite of each other – formed a depression, now known as Meadow Valley.

“Over time, the depression filled with water, creating a freshwater lake,” the Cathedral Gorge website explains. “Continual rains eroded the exposed ash and pumice left from the volcanic activity, and the streams carried the eroded sediment into the newly formed lake.”

Cathedral Gorge’s formation, made of silt, clay and volcanic ash, are the lake’s remnants.

“As the landscape changed and more block faulting occurred, water drained from the lake exposing the volcanic ash sediments to the wind and rain, causing erosion of the soft material called bentonite clay,” the park website notes. “Wind and water erode rocks and soils at a rapid rate and vegetation cannot grow on the outcroppings. The vegetation-free slopes stand in stark contrast to the valley floor where primrose and Indian ricegrass hold small sand dunes in place.”

The valley floor is also habitat for barberry sagebrush, narrow-leaf yucca, juniper trees, greasewood, shadscale, four-winged saltbush, and white sage. Rabbit brush grows in areas along the roadsides and walkways.

As visitors traverse the park’s trails, they will also see dark, bumpy patches around rocks and other plants. They should not step on this as it is cryptobiotic soil. The park website calls it “desert glue.” It is alive with bacteria, algae, lichens, mosses and microfungi.

“Cryptobiotic soil crusts help stabilize the soil by reducing wind and water erosion,” the park website explains. “These microcosms are fragile, easily damaged if disturbed and can take 100 years to recover from damage.”

Cathedral Gorge today

“Our big draw today is the slot canyons — they’re so unique,” Andone said. “They’re totally different from slot canyons you see in Utah.”

Today’s visitors love the beauty and the quiet in the park, Andone said. Cathedral Gorge, because of its remoteness away from an urban center, is a destination park. She said some remark that it reminds them of Badlands National Park in South Dakota, but Badlands does not have the slot canyons.

Cathedral Gorge is in an area with four other state parks within a 50-mile radius, all with different altitudes, biomes and ecosystems, Andone said. Of all five, however, Cathedral Gorge is the most well-known and most visited. That increased visitation is one of its main challenges today.

Andone said that when she started in 2009, the park hosted approximately 35,000 visitors. Today, about 100,000 visit each year. The park is having to accommodate triple the visitors it did just over a decade ago with the same amount of staff. Lack of funding is what is preventing the park from hiring more staff to better accommodate its rising visitation.

A few years ago, there used to be months, especially the hotter summer months and colder winter months, when the park saw very little visitation. That doesn’t happen today, Andone said.

Another challenge for the park is deferred maintenance. They’re trying to upgrade infrastructure in the park, but don’t have the funds to do much. For instance, there is a 50-year-old bathroom that needs to be replaced, Andone said, and they’d like to expand the 26-site campground, which is nearly always at capacity and more (with an overflow area) from Presidents Day to early June and September to Thanksgiving. The park, unlike many national parks, does not have a non-profit partner to advocate for it and raise money for improvements.

“We’re totally fee dependent,” she said.

The park does not receive any federal money and does not receive much from the state general fund. The park is in a Catch-22 situation, she explained, in that it needs the visitation to raise money but has a hard time accommodating that visitation because of funding and staffing shortages.

Andone said the park thankfully doesn’t have to deal with the graffiti that Valley of Fire does since it is not close to an urban center like its southern counterpart.

One problem the park does face though is visitors not cleaning up after their dogs, which Andone said is a reason why dogs are prohibited in most national parks. Nevada state parks are dog friendly and she said that is a comment she regularly receives from guests — that they’re glad they can bring their canine companions along with them. Most are really good about cleaning up because they want to keep the park dog friendly, Andone said, but a small percentage aren’t.

Cathedral Gorge is an approximate hour and forty-five minute drive northwest of St. George via state Route 18, then state Route 56, which becomes state Route 319 after crossing into Nevada. Visitors can park and enjoy walking around to explore the unique scenery and slot canyons. Visitors should also not miss the view from Miller Point, which is also a trailhead to a path that descends down into the lower canyon.

For more information about Cathedral Gorge, visit the park’s website.

Click on photo to enlarge it, then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

This historic photo shows Nevada Congressman James Scrugham, who served as governor during the mid-1920s, speak at the dedication ceremony of Cathedral Gorge State Park, Nevada, 1934-1935 | Photo courtesy of Cathedral Gorge State Park, St. George News

This historic photo shows members of the Civilian Conservation Corps constructing the bowery at Miller Point in Cathedral Gorge State Park, Nevada, 1934-1935 | Photo courtesy of Cathedral Gorge State Park, St. George News

This historic photo shows members of the Civilian Conservation Corps building a bathroom and picnic facilities, Cathedral Gorge State Park, Nevada, 1934-1935 | Photo courtesy of Cathedral Gorge State Park, St. George News

Today, Miller Point features a staircase that leads to a trail to explore the canyon down below, Cathedral Gorge State Park, Nevada, April 24, 2021 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Miller Point provides a stunning view of the spires and erosive spectacle of Cathedral Gorge State Park, Nevada, April 24, 2021 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The picnic area built by the CCC in the 1930s is an extremely scenic location to eat, Cathedral Gorge State Park, Nevada, April 24, 2021 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The picnic area built by the CCC in the 1930s is an extremely scenic location to eat, Cathedral Gorge State Park, Nevada, April 24, 2021 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The CCC-era water tower is the most striking remnant of the CCC's work in Cathedral Gorge State Park, Nevada, April 24, 2021 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The CCC-era water tower is the most striking remnant of the CCC's work in Cathedral Gorge State Park, Nevada, April 24, 2021 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The Cathedral Gorge landscape is unique in that no vegetation grows upon it, among other things, The picnic area built by the CCC in the 1930s is an extremely scenic location to eat, Cathedral Gorge State Park, Nevada, April 24, 2021 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

About the series “Days”

“Days” is a series of stories about people and places, industry and history in and surrounding the region of southwestern Utah.

“I write stories to help residents of southwestern Utah enjoy the region’s history as much as its scenery,” St. George News contributor Reuben Wadsworth said.

To keep up on Wadsworth’s adventures, “like” his author Facebook page, follow his Instagram account or subscribe to his YouTube channel.

Wadsworth has also released a book compilation of many of the historical features written about Washington County as well as a second volume containing stories about other places in Southern Utah, Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada.

Read more: See all of the features in the “Days” series

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2021, all rights reserved.