FEATURE — Anyone who knows U.S. history well knows that media and advertisements in the 1920s tended to sensationalize reality.

That was certainly true of the moniker given to Nevada’s “Lost City” during that time period, which was originally known as Pueblo Grande of Nevada by the archaeological team that excavated it in the mid-to-late 1920s. The more sensational name of Lost City is the one that has stuck.

However, today that name might not seem quite as sensational.

Pueblo Grande is essentially “lost.” The waters of Lake Mead cover most of it.

The information gleaned from the initial excavations was also “lost” to researchers for quite some time.

And finally, its museum is “lost” to many travelers who frequent Southern Nevada.

Lost City Museum Director Mary Beth Timm admits that most of the museum’s visitors “discover” the museum by chance while driving along Nevada state Route 169, otherwise known as Moapa Valley Boulevard, through Overton.

Timm said such visitors are delighted to find such an archaeological gem, with an actual archaeological site inside the museum itself and another one on the north side of the museum grounds, as well as replicas of others on the south side.

But unfortunately, visitors aren’t able to see the grandest of the ruins, which were the inspiration for the museum, because much of it is under water.

Discovery and early excavation

There had been references to Puebloan ruins in southern Nevada since the late 19th century, but it wasn’t until the early 20th century that the reports were confirmed.

James Scrugham, Nevada’s governor from 1923-1927, asked locals to be on the lookout for Native American remains. Brothers Fay and John Perkins from Overton recognized broken pieces of pottery and the outlines of ancient structures along the barren ridges near the confluence of the Muddy and Virgin rivers and the town of St. Thomas, which was originally settled by members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and was also flooded after the construction of the Hoover Dam.

The Perkins brothers reported the existence of the ruins to Scrugham in 1924, and excavations by a team of archaeologists from the Museum of the American Indian and the Heye Foundation (which was later absorbed by the Smithsonian) led by Mark Harrington began in November of that year after Scrugham’s insistence.

Scrugham became the driving force for the excavations, hoping to attract more tourists to the area, and his efforts led to national and international attention pointed towards the discovery. Scrugham even personally arranged site visits for newspaper and magazine writers, who were often given pieces of pottery and arrowhead fragments as souvenirs, according to an article in the Summer 2010 issue of “The Journal of Southwestern Anthropology and History.”

To capitalize on the fame, a Lost City Pageant was held in May 1925, complete with constructed replica of an Ancestral Puebloan dwelling.

Misinformation about Pueblo Grande, unfortunately, was widespread. Some of the most prominent exaggerations were that Pueblo Grande was the largest city in the Western Hemisphere in its heyday as well as the oldest city in the world. Another was that it was inhabited by 7-foot giants, which Harrington debunked in his writings about the excavation.

This was the start of near constant archaeological work occurring in the area until 1941, completed with the help of the Southwest Museum of the American Indian and the Civilian Conservation Corps. Work was halted because of two major factors — the filling of Lake Mead and the start of World War II, which obviously directed resources and national interest away from archaeology.

Previous to the discovery, archaeologists thought that the Ancestral Puebloan people were concentrated in the Four Corners area, but Pueblo Grande proved that they thrived much farther west, becoming the westernmost discovery of the ancient people. The ruins provided valuable insights into how the Ancestral Puebloan people lived.

Harrington wrote an article about his findings which appeared in the July 1925 issue of “Scientific American.”

Harrington made it a point to mention that Native Americans were part of the big dig.

“It seems truly fitting that Indians should take part in the expedition of this sort, especially when Indians can be found who will take such a personal interest in the work and will give such careful and intelligent service,” Harrington said.

The excavation found numerous houses ranging from structures with only one or two rooms to more “pretentious” buildings, according to Harrington’s account, that contained 21 rooms.

The dig offered a solid snapshot of what life was like for these ancient people.

Residents of Pueblo Grande and the surrounding area “gathered wild natural products of the desert, such as mesquite beans and screw beans,” Harrington noted. They also farmed the valley lowlands, growing crops such as beans, corn and squash. The early Latter-day Saint settlers found old irrigation ditches as they cleared the land, evidence that the ancient peoples irrigated their crops.

For meat, the Ancestral Puebloans hunted deer and other game and raised no domestic animals except for dogs, Harrington wrote.

Apparently, the peoples who lived in the Pueblo Grande were excellent weavers. Harrington reported that his team succeeded in saving a few crumbling bits of fine woven cloth, which reveal that cotton could have been part of Ancestral Puebloans’ agricultural products (or was obtained through trade) and that they had also mastered the skill of dyeing textiles.

“Some of the pieces, in texture like cheese-cloth, still showed traces of color, red and blue and purple,” Harrington wrote.

These ancient peoples even weaved furs, as shown by evidence uncovered by Harrington’s team. The ancient people cut the furry skins of rabbits and other animals into long, narrow strips which were twisted and woven into blankets. They also used feathers to make cloth, which Harrington reported must have been a laborious process.

“It was necessary first of all to gather and prepare fiber, then twist it into strings, and then to wrap these strings with downy feathers until a soft, fluffy yarn was produced,” Harrington wrote. “Then came the less tedious labor of weaving this yarn into a blanket.”

These people also produced jewelry such as pendants of turquoise, selenite and shells, which almost certainly came from the Pacific Ocean, revealing that they engaged in intertribal trade.

Their arrow-points, drills and knives demonstrate they had nearly perfected the art of chipping stone, in Harrington’s opinion.

The archaeological team found pottery in abundance during the dig, much of which was plain black pottery. However, they also found more ornate pieces, including “bowls and jars of white, and gray and rich red color on which tasteful designs had been drawn with black paint,” as well as “pottery in which the decoration was worked out by varied corrugations of the outside surface.”

The most primitive of the dwellings Harrington and his team found were oval pits dug down into the earth to a depth of 2-3 feet, measuring 8-10 feet in length, while the later dwellings were rectangular and partitioned into separate rooms.

Harrington said in his article that the houses excavated date about to the time of Christ, but that the exact time might never be known.

The one break in archaeological work in the area was from 1931 to 1933 on account of the Great Depression. But work started up in 1934 with the Civilian Conservation Corps taking the lead — one company doing excavation and infrastructure work and one company building the museum. Fittingly, one of the last companies of men working on excavation to save the artifacts from being lost underneath the future Lake Mead was Fay Perkins, one of the men who originally reported the ruins’ discovery.

Those 1920s and 1930s excavators thought that Pueblo Grande would be under water in perpetuity, but some of it has re-emerged as Lake Mead has dropped. In fact, she noted that the whole town of St. Thomas was once completely underwater but has now re-emerged and interpretive panels were recently placed there with the anticipation that the town’s ruins would not be underwater again.

There have been excavations since then, but not quite to the same scale as the ones completed in the 1920s and 1930s, Timm said.

The early 20th century digs were the largest excavations ever undertaken in southern Nevada and large-scale excavations aren’t funded that much anymore, Timm explained. Without that archaeological work, she said, the Lost City could have been truly been lost forever.

More recent excavations

Those early 20th century excavations have been the main source of information about the Lost City, but many Southwestern archaeologists have been unaware of their legacy, as reflected by the absence of southern Nevada from many archaeological maps of the Southwest, Karen Harry and James Watson reported. Harry is a professor of anthropology at UNLV, and Watson is an anthropology professor at the University of Arizona as well as a curator at the Arizona State Museum. Both have been part of the most recent fieldwork.

The two authors note that early fieldwork was done by a multiplicity of organizations, leading to many of the materials collected and field notes written becoming scattered over the years. Another reason the early fieldwork is relatively unknown is the lack of a book on the findings, which was a major regret of Harrington, the two authors wrote.

Additionally, “because the Lost City excavations spanned the early half of the twentieth century, much of the data we would recover today was not collected,” Harry and Watson explained. “In 2005, archaeologists from Lake Mead National Recreation Area and the University of Nevada Las Vegas set out to remedy some of these shortcomings.”

This archaeological team completed excavations of “House 20” in what is known as the “Main Ridge community” to glean more information. One of the earlier excavations’ weaknesses was they were majorly concerned with searching and finding museum quality pieces and overlooked more mundane items such as ground stone items, pottery shards or chipped stone debris.

For instance, one of the findings of the 2006 fieldwork could be considered more mundane but revealed an interesting tidbit about Ancestral Puebloan life.

“The abundance of ash pits, burned bone, and midden deposits recovered during our excavations indicate that cooking regularly took place outdoors at this location,” Harry and Watson wrote.

One of the overarching conclusions with the new data collected was that “the inhabitants of House 20 were heavily invested in agriculture and utilized wild resources that could be obtained in the immediate vicinity,” they wrote.

Three of those “wild resources” included bighorn sheep, mule deer and rabbits. The two authors concluded that rabbits, being most abundant and easily caught, were a major source of food and that evidence indicates the Puebloans trapped cottontail and hunted jackrabbits in the surrounding desert. Sometimes these rabbits, as well as other small rodents, were easy prey because they were attracted to the Puebloans agricultural fields and engaged in what Harry and Watson termed “garden hunting.”

One of the major points of evidence supporting the early inhabitants’ dependence on agriculture is the large quantity of storage space in their dwellings, which, through macrobotanical analysis, showed to contain corn. The high proportions of cob fragments suggest that the Puebloans used corn cobs for fuel, Harry and Watson explained.

But even though the 2006 excavation added interesting information for a better overall picture of daily Ancestral Puebloan life, Harry and Watson cautioned readers that the insights were only from one site and only represent one time period. More investigation will be necessary to understand how these ancient people lived during different time periods and in different locations.

The museum

The Civilian Conservation Corps built the original museum as well as the replica Pueblo houses on the foundations of actual ruins in the mid-1930s. The CCC constructed the museum to resemble a Pueblo dwelling, with a later wing constructed to cover an authentic pit house.

Originally, it was called the Boulder Dam Park Museum, but later changed to Lost City Museum to conform to the more popular and accepted name.

“We are the only state museum actually on top of ruins,” Timm said.

The museum’s displays show visitors a timeline of Puebloan chronology and provide a snapshot of what these forebears of today’s Native American tribes faced to survive.

When the National Park Service turned operation of the museum over to the State of Nevada in 1952, it took everything that was on display. The State turned to private collections for artifacts for exhibits and purchased the items in 1973, Timm said.

About a third of the original artifacts found during the early excavations have been in a repository in Reno, but last year they were moved to a repository in the Las Vegas area, she explained. None of those items are on display yet.

Regardless of what specifically is on display, the museum provides a fascinating snapshot of the region’s ancient inhabitants. Its displays include pottery, baskets and arrowheads and other artifacts utilized by the Ancestral Puebloans.

A trip to the Lost City Museum would make an ideal companion visit to Valley of Fire State Park and the ruins of the St. Thomas ghost town.

For more information about the museum, visit its website.

Photo gallery follows below.

About the series “Days”

“Days” is a series of stories about people, places, industry and history in and surrounding the region of southwestern Utah.

“I write stories to help residents of southwestern Utah enjoy the region’s history as much as its scenery,” St. George News contributor Reuben Wadsworth said.

For previews on Days Series stories, insights on local history and information on upcoming historical presentations, please “like” Wadsworth’s author Facebook page.

Wadsworth has also released a book compilation of many of the historical features written about Washington County as well as a second volume containing stories about other places in Southern Utah, Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada.

Read more: See all of the features in the “Days” series

Click on photo to enlarge it, then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

Days series author Reuben Wadsworth's daughter explores the replica pueblo south of the Lost City Museum, Overton, Nev., March 10, 2016 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Days series author Reuben Wadsworth's daughter explores the replica pueblo south of the Lost City Museum, Overton, Nev., March 10, 2016 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Actual Ancestral Puebloan pithouse located on the grounds of the Lost City Museum, Overton, Nev., Oct. 1, 2018 | Photo courtesy of Lost City Museum, St. George News

A replica pueblo built on the foundation of actual ruins on the south side of the Lost City Museum, Overton, Nev., June 12, 2017 | Photo courtesy of Lost City Museum, St. George News

Exhibits of Ancestral Puebloan pottery in the Lost City Museum, Overton, Nev., Dec. 30, 2017 | Photo courtesy of Lost City Museum, St. George News

The front entryway of the Lost City Museum, Overton, Nev., Oct. 1, 2018 | Photo courtesy of Lost City Museum, St. George News

A female mannequin positioned as if she is grinding corn next to a pit house at the Lost City Museum, Overton, Nev., June 12, 2017 | Photo courtesy of Lost City Museum, St. George News

Pottery on display at the Lost City Museum, Overton, Nev., Dec. 18, 2017 | Photo courtesy of Lost City Museum, St. George News

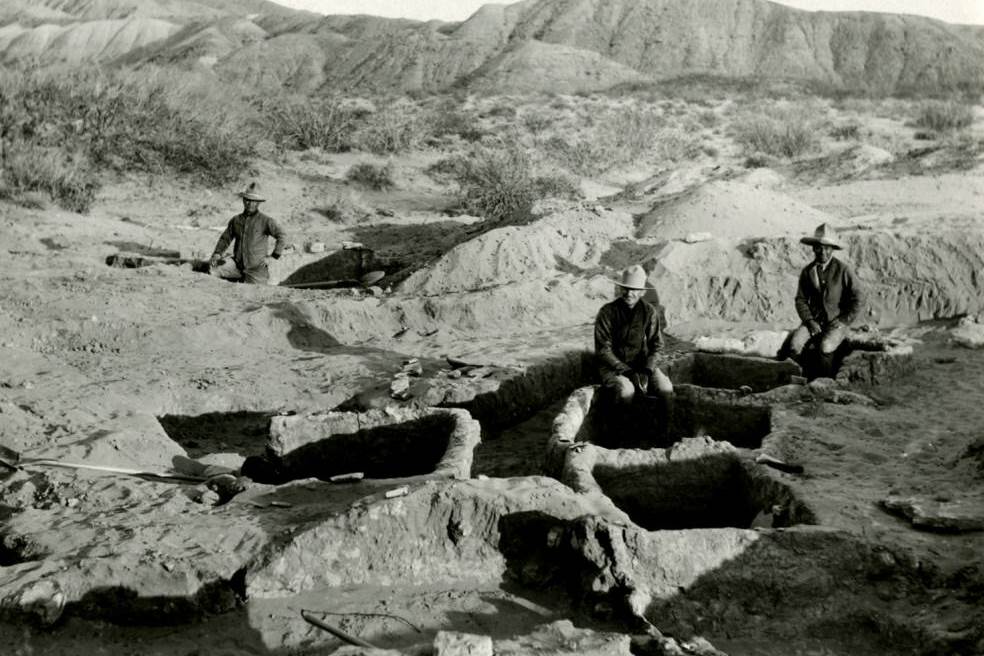

This historic photo shows early excavations of Pueblo Grande de Nevada, otherwise known as Lost City, near Overton, Nev., circa 1925-1929 | Photo courtesy of UNLV Library Special Collections, St. George News

This historic photo shows a portrait of John Perkins, one of the brothers who originally confirmed the existence of the Lost City ruins, near Overton, Nev., circa 1926 | Photo courtesy of UNLV Library Special Collections, St. George News

This historic photo shows early excavations of Pueblo Grande de Nevada, otherwise known as Lost City, near Overton, Nev., circa 1925-1929 | Photo courtesy of UNLV Library Special Collections, St. George News

This historic photo shows the exterior of a replica of an Ancestral Puebloan dwelling replica built for a pageant held to promote Lost City in 1925. The re-creation was dismantled before being flooded by the waters of Lake Mead, near Overton, Nev., circa 1935-1950 | Photo courtesy of UNLV Library Special Collections, St. George News

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews