ST. GEORGE — Raising a child is difficult under the best of circumstances. Being a single parent only compounds the challenges. And when you are the single parent of a child with autism, the job can often seem insurmountable – but Megan Thacker, who raised her infant autistic son for four years as a single mother, says the struggles and successes have given her a new outlook on life, and she feels lucky for the experience.

Thacker’s story first came to the attention of St. George News when she sent an email expressing her frustration with a story published in August about Aiden Nuzzo, a 7-year-old boy with autism who drowned in the pool of Sands Hotel in St. George.

“This article has troubled me from the moment I read it,” Thacker wrote. “I generally enjoy following St George news on Facebook because I can count on you to provide accurate and relevant news reports. This article, however, cut deep.”

While Thacker acknowledged that she thought everything in the article was true, she said she felt like the actions of the mother were unfairly put under the microscope and judged by others who didn’t understand either the mother’s struggles or the nature of autism spectrum disorders.

“I don’t know if people really understand how much a child with autism is drawn to water,” Thacker said in an interview with St. George News.

“If a parent has a child that’s not disabled,” she continued, “if that parent isn’t paying 100 percent attention, the kid’s usually not going to run and jump in the pool.”

The numbers match Thacker’s assertion. Between 2009 and 2011, the National Autism Association reported that approximately 90 percent of reported deaths of children 14 and under with autism could be attributed to accidental drowning.

These deaths are often the result of their “eloping tendencies,” something which is four times more present in children with autism than in those without and is a tendency present in Thacker’s son, Shane, as well as the boy who drowned.

“You could be doing everything you possibly could for that child in a perfect situation or way better setting (than the hotel where Nuzzo was staying),” Thacker said, “and they still find a way to get out.”

Other signs and struggles

Autism spectrum disorders represent a wide range – or “spectrum” – of developmental disorders that impair an individual’s ability to communicate or interact.

Autism affects approximately 1 out of every 68 children and is more common in boys than girls.

The attraction to water is only one of the traits common to many children with autism, said Barbara Anderson, owner of Summit Behavior Services in St. George.

“Those on a spectrum tend to struggle with social skills, anxiety, focus,” Anderson said. “They tend to have heightened senses. They might be very sensitive to touch, sound, smell, sight.”

Thacker understands this all too well with her son, Shane; however, she didn’t pick up on it at first. As Shane was her first baby, she didn’t notice anything that might have been considered unusual.

“I didn’t know that he was autistic,” Thacker said. “He seemed like everything was normal. … He seemed developmentally as a baby like everything was fine. He was totally healthy, and he was a happy baby.”

However, not long after Thacker stopped breastfeeding Shane when he was about 16 months old, he stopped eating. At his 18-month well-baby checkup, the pediatrician noted other developmental delays, including late crawling and talking.

“I was kind of in denial about it,” Thacker said. “I was like, ‘No, everything is fine.’ I just didn’t know what to do about it. He wouldn’t eat any food at all. … He just wanted something to drink and that was it.”

The real blow, Thacker said, was when the pediatrician questioned her about it, something which felt like an attack on her parenting skills.

“His pediatrician at the time was kind of like, ‘Aren’t you feeding him?’ That why-aren’t-you-taking-care-of-your-kid attitude,” she said, “it felt like all I did all day was try to get that kid to eat.”

Eating problems are common for children with autism, Anderson said. With their heightened senses, they often have a hard time with the taste and texture of food.

“A lot of times when they’re on the spectrum, they prefer just two or three basic foods, and they don’t want to try something else,” Anderson said. “With the heightened tastes, there might be too much flavor, and they don’t want that. Or it could be the texture of the food that makes them turn away or gag on it.”

Another familiar behavior of children with autism that can also lead to misconceptions about parenting skills or the disorder itself, Anderson said, is their tendency not to look someone directly in the eyes or respond to requests immediately. As a result, many of these children are labeled “defiant” or “discipline problems.”

“They are processing so many things, it’s very difficult for them to look you in the eyes,” Anderson said. “Whereas we can look at someone in the eyes and see their eyes, they are seeing all kinds of things, and it’s very difficult for them to tune it all out to hear what you’re saying. So they tend to look at you in their peripheral vision … I try to make people become aware that if they’re looking at you out of the side of their eyes, they are looking at you in the eyes.”

Regarding response time, Summit Behavior Services has a rule that staff members must give a client with autism at least seven to 10 seconds to respond to a request. Within that 10 seconds, they should begin to respond. Without that time to process, she said, problems can arise. Anderson said:

What happens is, when they don’t respond within the first couple seconds, we tend to repeat ourselves. ‘Hey, you need to put your backpack away.’ And then they don’t respond for the next couple seconds and we say it again with frustration. … Every time you’re doing that without waiting that 10 seconds, they are restarting that processing. When you do that over and over like that, what tends to happen is you’re going to trigger behaviors. They’re going to be so frustrated with you because they’re halfway into the processing and you just restarted them. And then your frustration is coming through.

While this behavior is seen as simply a disruption in a classroom, it can often have fatal consequences in the real world, Anderson said, and it reflects a fear held by many parents of children with autism.

According to a March 2016 report from the Ruderman Family Foundation, approximately a third to half of all people killed by law enforcement have some form of disability. Anderson got choked up as she recalled the story of a man in Ohio who was killed by police officers.

“They didn’t know he had autism. They didn’t understand,” she said. “It makes me emotional because it was very difficult to see this news article and watch that film, as I have grandchildren on the spectrum and I have a deep love for those on the spectrum and understand their difficulties.”

That set the autism community buzzing, Anderson said, and hit home to the fears of the parents.

“They were making comments (on the support group chats) like ‘I have a teenager who is going to be getting their driver’s license and this scares me to death because if a police officer pulls them over, he won’t look at them in the face, and is that going to happen to him?”

Following the incident in Ohio, Anderson said she was very impressed that St. George Police Detective Derek Lewis contacted Bonnie Webb, who is Anderson’s daughter, as well as the founder and president of the Southern Utah Autism Support Group.

“(Lewis) said, ‘Will you please come and educate our police officers on autism so this doesn’t happen here?’”

Anderson went on to say that Lewis has worked “tirelessly” with Webb and the autism community.

Other successes, support groups and superheroes

Even though Thacker was a single mother with Shane from the time he was 5 months old until meeting Quinn Thacker, a “very patient and supportive” stepfather for Shane, she said one thing that distinguished her from Celia Nuzzo, the mother in the St. George News story, was that she had help from her family during those formative years.

However, Thacker admitted to having similarly experienced her own struggles with depression and substance use.

Anderson said these struggles are common in these situations, especially given the fact that children with autism will only sleep in short blocks of time.

“These families that are struggling so much, they have to be up 24 hours a day, taking care of their children who aren’t sleeping,” Anderson said. “They are running on empty. They are exhausted. … That article (about Nuzzo), there was a lot of conversation and judgment about that parent being on substances. This kind of lifestyle can turn families to that, just to be able to cope and to be able to keep up.”

Anderson said that she doesn’t condone the use of substances but hopes that with the proper support, those parents or caregivers can be guided in healthier directions for coping.

“Celia Nuzzo needed the help that I got,” Thacker wrote in her original email, “and she did not receive it. Not at all.”

For this reason, Thacker said she is thankful for groups like Southern Utah Autism Support Group, which provide a forum to both help and be helped.

“Support groups are the best,” she said. “You can hear that other people are dealing with some of the same things, but then you can also contribute. Instead of struggling so much with your situation, you can actually use it to help somebody else. That’s been a huge positive for me.”

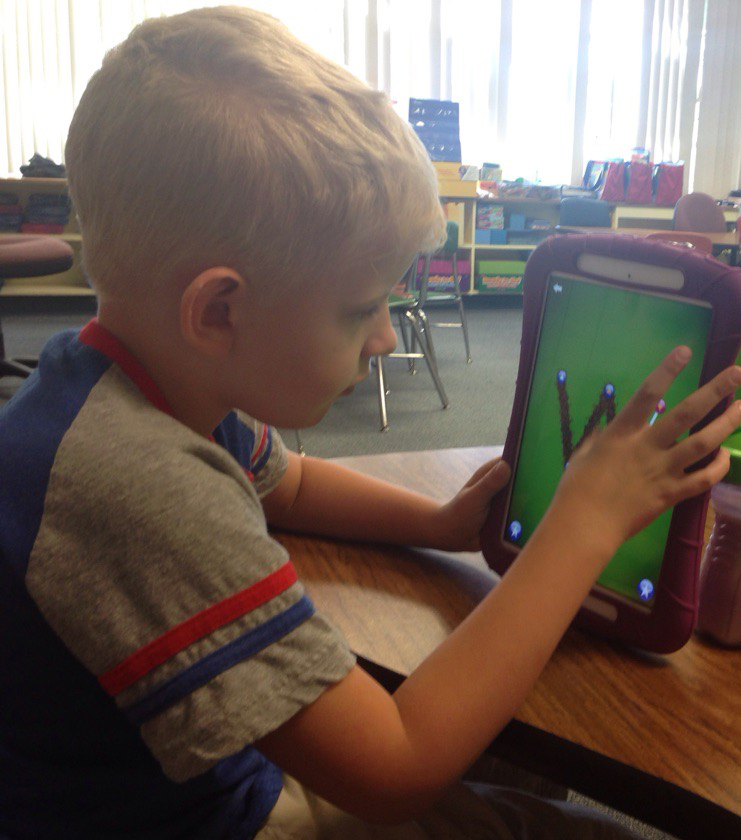

Another positive has been Shane’s experience at Summit Behavior Services, Thacker said, where they developed a program specifically catered to his needs.

This is just one part of how Summit approaches treatment, Anderson said. She listed several successes they have had with clients, from simply trying new foods to being able to leave the home to go in public.

“Parents will cheerfully say to us … ‘We got to take our children to a family Christmas party for the first time in years, and they actually got to meet their relatives.’”

Part of the key to this success, Anderson said, is to find each client’s “super power.”

“Because of their heightened sensories, they may excel above and beyond in math, in computers, in music, in reading, in writing,” she said. “They all seem to have something they excel at, and we call that their super power. And we feel its our job to hone in on that super power, while at the same time helping them learn to control this body that they can’t figure out how to control that’s causing them so much discomfort. … Also, at the same time, recognize that they have amazing gifts and focus on what they can do right instead of what they can’t do.”

This realization was important for Thacker not only in relation to Shane, she said, but also in regards to her own parenting.

“For a long time, I was really struggling and really unhappy, and I didn’t know how to cope,” she said. “I didn’t feel like I was adequate or good enough as a parent.”

Thacker said coming to terms with her life led to a change for the better.

“Shane’s autistic, and I can’t change that,” she said. “Once I got to a point where I accepted that, I started realizing that he is amazing and perfect how he is, and that I don’t need to change that. There’s not really anything to fix. That was a turning point.”

“He’s a happy kid. He’s so sweet. I feel like I’m really lucky to have him.”

For more information on local autism resources, go to the Southern Utah Autism Support Group website.

For a complete list of Summit Behavior Services programs, click here.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2016, all rights reserved.