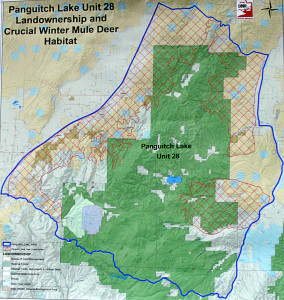

FEATURE – In an effort to control the population of Panguitch mule deer from the Division of Wildlife Resources’ Unit 28 (see map inset), which far exceeds the acceptable limit of 8,500 designated by the Department, collaborative researchers began to translocate the deer in 2013. What happened next was beyond all expectations.

Surprising results

Researchers anticipated high mortality rates for the translocated deer, but results have exceeded their expectations. Not only are the deer surviving the move, but the ones who survive are thriving in their new environment.

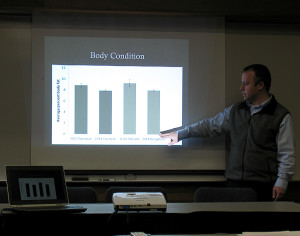

BYU Department of Plant and Wildlife Sciences Associate Professor Randy Larsen spoke to a room full of interested community members, DWR representatives and Sportsman for Fish and Wildlife members Feb. 27 at the Southern Utah University Hunter Conference Center to share what researchers have learned through the past two years of the study.

While the DWR project is funded by Sportsman for Fish and Wildlife and executed by the wildlife resources division, tracking the progress and data from the study has been Larsen’s responsibility.

In 2013 there were a total of 102 deer captured in January and March, 51 each time. The deer were moved from Parowan to central Utah. In 2014 there were 98 deer captured in two loads and moved to central Utah.

The survival rate of the deer in 2013 was fairly low at only 50 percent, Larsen said, which was still higher than expected. In the second year, another 10 percent of the translocated deer from 2013 died, raising the mortality rate to 60 percent for the entire 2013 herd.

The 98 deer that were moved in 2014 had about 76 percent survival in their first year however, proving that translocation could potentially be a viable option to both controlling overpopulated areas and reestablishing mule deer populations in areas where there has been a decline.

“This part is really interesting,” Larsen said. “Despite being moved, despite wandering really far during the summer, they were just as fat, or even a little better than Parowan deer during 2014.”

The deer moved around quite a bit more than the resident deer that were already in the area they were deposited into, Larsen said, but site fidelity remained constant, which is a good indicator of deer behavior, in a normal fashion despite the stress of being moved to a location that was unfamiliar to them.

“That, in my opinion, is the most important positive finding in this project,” he said. “The high site-fidelity.”

Dwindling habitat

The population objective for the Panguitch deer that winter graze in the Parowan Valley is somewhere around 8,500 and it’s been well above that for several years. The state is mandated by law to regulate the population objective, and with the numbers averaging closer to 11,700 in 2013 and 2014, the grazing habitat has suffered greatly.

In the Cottonwood area of the Parowan Valley range, there is a series of three enclosures built to study the depletion of range habitat. Bureau of Land Management and DWR biologists are using the enclosures to compare range habitat at various levels of grazing.

In one section, livestock are restricted from grazing. In the next section, deer and livestock are restricted, but rabbits are permitted to graze. In the last section, all grazing is restricted.

“There is a fenced area that is a high fence, probably 7 (to) 8 feet,” DWR biologist Jason Nicholes said. “And it restricts everything, deer, livestock, it even has a fence around the bottom made of chicken wire and it restricts rabbits.”

This gives scientists a good idea of exactly which grazing animals are causing the most degradation to the surrounding vegetation. Researchers have found that there is little to no difference between the area outside of the enclosure where all animals can graze, and the area inside where only livestock are prohibited from grazing.

This has led them to believe that deer are the largest source of depletion of habitat, Nicholes said.

In the uncontrolled area allowing all animals graze (left photo), innumerable deer grazing have depleted available natural resources, whereas in the controlled area restricting all grazing (right photo) there is a healthy habitat.

Controversy

One solution to the overpopulation problem is to allow a larger harvest of deer each year, Nicholes said, but with so many deer the harvest would consist primarily of does and that is an unpopular solution. Does produce bucks, and sportsmen want bucks available to them during the hunting season, so it becomes a vicious cycle that is not the most viable option.

Not everyone agrees with the chosen direction of population control by DWR, United Wildlife Cooperative member LeGrande “Lee” Tracy said. Opening the hunt to include more does could potentially open new doors to groups like his, allowing them to start a youth sportsmen program that would introduce young hunters to the tradition.

“Shooting a doe is substantially easier than shooting a buck,” he said, explaining why it would be a great way to begin training youth. “They are not so spooky, and you can see how easily they are catching them with the helicopter.”

It’s not so much the idea of removing the does from the range and moving them elsewhere that is bothersome to him, Tracy said. The methodology seems counterproductive from the ultimate goal of population reduction, because DWR is only moving 100 mule deer at a time.

In 2012, Tracy said, DWR took representatives from United Wildlife Cooperative and Sportsman for Fish and Wildlife on a trek through the valley to share the depletion of habitat and discuss the overpopulation issue. When DWR was questioned about the idea of relocating deer, he said, they told him they would have to move 500 deer once a year for five years.

Funding for the entire project has been provided by Sportsman for Fish and Wildlife. Tracy said he believes that is why DWR has put off raising the number of doe tags during doe season.

“As soon as they made that offer,” Tracy said, “we could not get either party to raise their numbers to get to the 500 – they didn’t want any more doe tags and they weren’t going to move anymore deer.”

Between the 100 deer moved each year and the 150 doe tags sold, DWR is reaching about half of the yearly requirement to reduce the population Nicholes said. While that is not sufficient to reduce the herd, he said, the numbers have stabilized for now, which is a good sign.

“We probably would consider increasing permits,” Nicholes said. “SFW said, ‘Well, we’d like you to transplant the deer, and we will pay for it if you guys don’t increase permits,’ and that’s where we’re at right now.”

Now that there has been some success in stabilizing the deer population, Nicholes said, the future could include an increase in available tags.

“If we have a hard winter,” he said. “Then we probably should look at moving more deer, or having more tags, or both.”

Moving day

On March 5 and 6, DWR, Sportsman for Fish and Wildlife, United Wildlife Cooperative, Helicopter Wildlife Services and BYU researchers met up once again in Parowan to capture and move as many deer as possible.

One trip after another, the helicopters would fly in dangling two to three does, one beneath the other in slings that are specially made to carry them. The helicopter pilot would gently set the does down, eyes blindfolded and legs bound, one at a time until all of the does were on the ground for release in short order.

Hobbling and blindfolding the deer is a safety practice to protect both the deer and the researchers studying them from injury.

Each doe was swiftly gathered by volunteers, and carried on a gurney to a makeshift clinic where researchers were ready to quickly assess the health of each doe before releasing them into the back of a trailer for transport to central Utah where the mule deer population has declined.

Does were tagged, weighed, checked for fat content, age and overall health. Biologists drew blood and then the does were slid into the back of the transport trailer to remove the bindings and blindfolds so they could stand on their own.

A total of 78 does were captured studied and transplanted over the course of the two days the collaborative group spent in the Parowan Valley this year.

While this is the third year of the translocation study, Nicholes said, there is no projected time frame for terminating the study.

“It’s a year-to-year project,” he said.

Click on photo to enlarge it, then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

BYU Department of Plant and Wildlife Sciences Associate Professor Randy Larsen spoke to a room full of interested community members, Southern Utah University Hunter COnference Center, Cedar City, Utah, February 27, | Photo by Carin Miller, St. George News

BYU Department of Plant and Wildlife Sciences Associate Professor Randy Larsen spoke to a room full of interested community members, Southern Utah University Hunter COnference Center, Cedar City, Utah, February 27, | Photo by Carin Miller, St. George News

Map of winter grazing areas for the Unit 28 mule deer, Southern Utah University Hunter COnference Center, Cedar City, Utah, February 27, | Photo by Carin Miller, St. George News

Map of winter grazing areas for the Unit 28 mule deer, Southern Utah University Hunter COnference Center, Cedar City, Utah, February 27, | Photo by Carin Miller, St. George News

Volunteers stop for a break while waiting for another helicopter load of deer, Paragonah staging area, Paragonah, Utah, March 5, 2015 | Photo by Carin Miller, St. George

Volunteers and researchers carry deer on gurneys into the assessment tent, Paragonah staging area, Paragonah, Utah, March 5, 2015 | Photo by Carin Miller, St. George

Researchers assess the health and age of a mule deer from unit 28, Paragonah staging area, Paragonah, Utah, March 5, 2015 | Photo by Carin Miller, St. George

Volunteers and researchers carry deer on gurneys into the assessment tent, Paragonah staging area, Paragonah, Utah, March 5, 2015 | Photo by Carin Miller, St. George

Wildlife Biologist Jason Nicholes, Paragonah staging area, Paragonah, Utah, March 5, 2015 | Photo by Carin Miller, St. George

Volunteers help to load recently captured mule deer doe into the back of the relocation trailer after being examined, Paragonah staging area, Paragonah, Utah, March 5, 2015 | Photo by Carin Miller, St. George

DWR Wildlife Biologist Jason Nicholes releases recently tagged doe into the back of the trailer for relocation, Paragonah staging area, Paragonah, Utah, March 5, 2015 | Photo by Carin Miller, St. George

Related stories

- On location with researchers; 4-year fawn survival study begins final year

- When big horn sheep fly; STGnews Videocast

- Deer captured on Antelope Island, released in Southern Utah

- DWR launches massive patrol effort against deer poaching

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2015, all rights reserved.