ST. GEORGE – Recovery efforts for the endangered Southwestern willow flycatcher are progressing steadily, complicated by efforts at controlling the nonnative tamarisk.

“Overall recovery of the flycatcher population in Washington County is heading in the right direction, but is moving at a slow pace,” said Christian Edwards, a wildlife biologist with the Washington County Field Office of the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources.

“We are working towards a goal of 30 pairs in Washington County,” Edwards said.

As biologists increase the amount of available breeding habitat, increasing numbers of flycatchers are hoped for.

The Southwestern willow flycatcher (Empidonax traillii extimus) is a small songbird placed on the federal endangered species list in 1995 by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. It is threatened by habitat loss and is thought to thrive best in a native mix of willows, cottonwood and seep willows.

When monitoring and recovery efforts began in Washington County in 2008, there were only eight breeding pairs of the flycatchers. Between 2008 and 2013, the numbers fluctuated between seven and 10, however, in 2014, there were 13 successful nest sites.

“It’s hard to say (why), we would like to think it’s because of our restoration efforts, the work that we’ve done providing more suitable habitat for the birds,” Edwards said.

Habitat issues

Recovery efforts in Washington County have been very successful in recovering suitable flycatcher breeding habitat. The greatest threat to the flycatchers is habitat loss and fragmentation, Edwards said.

Biologists have seen a shift in the preferred nesting habitat of the flycatcher, as efforts at tamarisk control have started to succeed.

The tamarisk, also called the saltcedar or salt cedar, is a nonnative, invasive species that is generally considered a threat to native flora and fauna as well as a flood and fire risk.

A multiagency effort to gain control over the proliferation of the tree has included the release of a biological control, the tamarisk beetle, in 2006, along with mechanical removal of the invasive tree.

However as the beetles multiplied in numbers and began defoliating stands of tamarisk, it caused concern for the welfare of the flycatchers.

During two of the last seven years, the beetles caused the tamarisks to drop their leaves on a massive scale, right in the middle of nesting season, Edwards said.

“The beetles eating the leaves exposes the nest,” Edwards said. “Not only to predators, but also to the sun.” The result is higher temperatures, lower humidity, and exposure to predators, all of which can decrease the birds’ reproductive efforts, he said.

This can cause problems for the birds, because the loss of cover changes the microenvironment at the nest; raising the temperature, lowering the humidity, and exposing the nest and brood to predators.

“That has decreased hatching success … and predators can see the nest,” Edwards said.

As time went on, however, the flycatcher changed its habits.

“Because of the tamarisk beetle we saw a major habitat shift, which initiated in 2010,” Edwards said. As the tamarisk died, the willow regrew, and the flycatcher started nesting in the willow instead.

Biologists studying the flycatcher found that a mixture of willow and tamarisk is best suited for the flycatcher. In mixed coyote willow and tamarisk, the nests are much better hidden from predators than in areas with just a single tree species, Edwards said.

Tamarisks are valuable when mixed with native vegetation, Edwards said. Now, the goal in flycatcher habitat rehabilitation is to reduce tamarisk density by 60-70 percent, and replant thinned areas with a mix of native species that provide understory structure, plants such as coyote willow, cottonwood and seep-willow.

Cowbird problem

The brown-headed cowbird is also a problem for the Southwestern willow flycatcher, as it parasitizes the flycatcher by laying eggs in its nest, Edwards said. Cowbird eggs hatch earlier than the flycatcher, and the young birds grow faster than flycatcher nestlings.

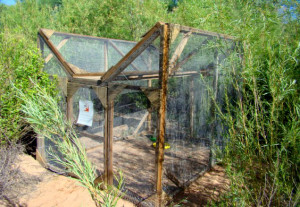

Cowbirds are native, although their area may be expanding. Efforts at controlling the cowbird problem include trapping the birds near existing flycatcher nests, Edwards said.

Habitat restoration and rehabilitation efforts for the endangered flycatcher have been focused on a 4.5 mile stretch of the Virgin River, and the recovery area includes population surveys, nest monitoring, and microhabitat and vegetation studies.

All of the known nesting sites in Washington County are located in a few places along the Virgin River, in St. George and Washington, Edwards said.

“They’ve been monitored since the 1990s, they were doing surveys from all the way up in Zion, all the way down into Arizona,” Edwards said. “We’ve narrowed it down to this region of the Virgin River, pretty much in the St. George area.”

In total, there are estimated to be between 1,000 and 1,200 breeding pairs of the Southwest willow flycatcher in existence. The largest part of the flycatcher’s range is in Arizona and New Mexico; but it includes parts of Utah, Colorado, Nevada, California and Mexico. The flycatchers migrate south in the winter to Mexico and Central America.

Related posts

- Agencies optimistic about tamarisk removal

- Commission protests forest service activity over grazing; call for county involvement

- Prairie dog management up for review; officials encouraged by progress

- County applies for HCP permit renewal, moves forward on land exchanges; STGnews Videocast

- Land use advocates ask Hatch to resolve land issues in tortoise habitat, eliminating Sand Mountain land swap

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2015, all rights reserved.