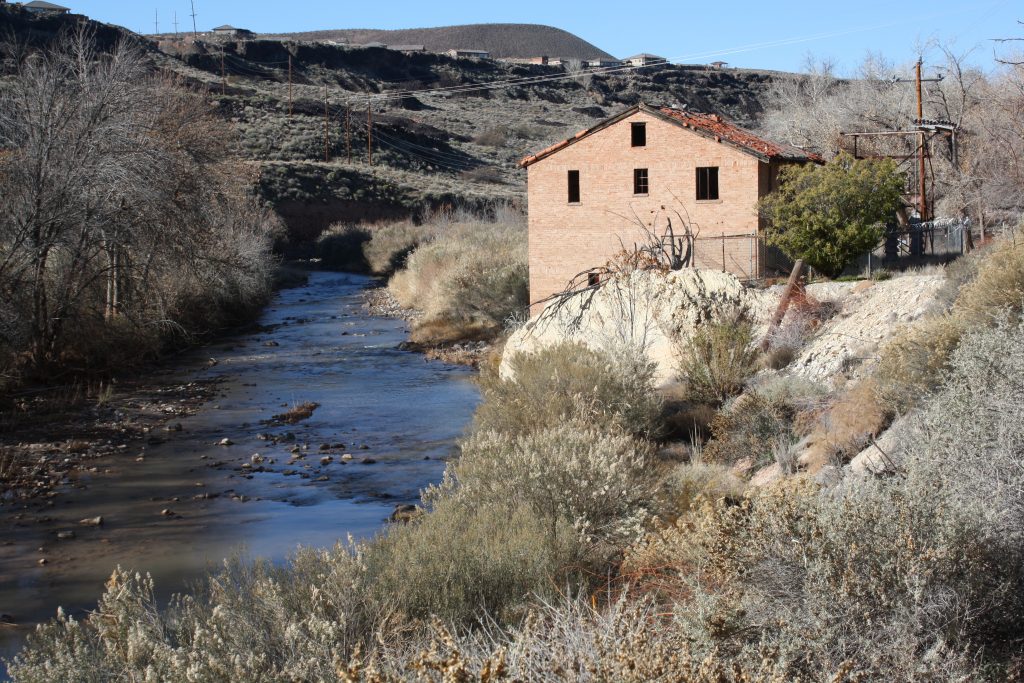

FEATURE – There is a building astride the north bank of the Virgin River easily seen while driving state Route 9 just north of the LaVerkin-Hurricane Bridge.

Many of the uninitiated in Southern Utah lore probably ask the same question while driving by: “What was that building used for?”

The answer is believe it or not, it was once a hydroelectric plant.

There are other structures and remnants of structures hikers can see along the trails in Confluence Park, where LaVerkin and Ash creeks feed into the Virgin River. Most are from just last century, but one is from many centuries ago — a Native American cave dwelling, which provided shelter to a group of people known as the Virgin Anasazi. An archaeological excavation revealed evidence of their lifestyle, including tools, weapons and crude ropes made of hair and rawhide.

Later on, the Paiutes inhabited the area and grew corn, squash, melons and other crops through limited irrigation.

Two sets of Caucasian explorers reached the area much later — the Dominguez and Escalante expedition in 1776 and Latter-day Saint apostle Parley P. Pratt with his Southern Utah exploring party in 1849.

After Toquerville was established in 1858, the confluence area was used for cultivation once again. Levi Savage Jr., who moved to Toquerville in the early 1870s, grew corn, sugar cane and lucerne, a type of alfalfa. In his journals, he referred to the area as “River Field” and writes about hauling hay, planting carrots, bringing home wood, cutting lucerne and repairing fences.

After Hurricane and LaVerkin were settled in the early 20th century, the area saw two other distinct uses — power generation and dairy farming.

The hydroelectric plant

When thinking about hydroelectric plants, usually the big ones like Hoover Dam or Glen Canyon Dam come to mind, but there were smaller operations as well.

In 1928, a permit was granted to Dixie Power to build an 899-kilowatt capacity hydroelectric plant at an approximate cost of $90,000 on the bank of the Virgin River. According to news reports of the time, construction commenced in December 1928 and by April 1929, the plant was operational. The power company cemented the ditch and provided a caretaker for the canal in return for half of the water flowing through it.

Construction of the plant included laying approximately 1,000 feet of 42-inch wood pipe. Water channeled from the LaVerkin Canal rushed through that pipe, with a lot of help from gravity, to power the hydroelectric generator. The water started in the Virgin River, was diverted briefly, and ended up right back in the river, just farther downstream. A man named Fred Brooks was the first plant operator, and, at first, he lived in the upstairs of the plant with his family.

The plant underwent many upgrades over the years, including the wood pipe being replaced with a metal one, as well as upgrades in the power plant machinery, semi-automating it so that its operator would not have to live on the premises.

The plant’s output was about the same as Hoover Dam’s small generator, which supplies power for the dam’s use. It was the largest plant in the network of four hydroelectric plants within Washington County and early on provided all the electricity needed for Hurricane, LaVerkin, Toquerville, Virgin, Rockville and Springdale, a 1975 Spectrum article by Richard Howard noted. The other plants in the county were in Veyo, Gunlock and Sand Cove, on the road between Dammeron Valley and Gunlock. If all four plants were offline, it was the LaVerkin facility that had to be started up first.

“Electricity was generated when water under high pressure was fed over a Pelton wheel, which was connected to a generator,” Victor Hall noted in his compilation, “Selected Topics Related to Hurricane, Utah.” “A Pelton wheel resembles an old fashioned water wheel rather than the turbines used at Hoover Dam.”

Designed to run within a specific range of revolutions per minute, the wheel “could literally throw itself to pieces,” Hall noted.

“When the generator was producing electricity, the resultant friction kept the Pelton wheel at a safe speed,” Hall wrote. “If, however, the generator was turned off, the Pelton wheel would soon reach catastrophic speeds.”

To prevent the wheel from spinning into oblivion, the power company installed a shunt that would automatically drop down when the power went off to divert water coming through the pipe back out into the river channel.

When the wheel was damaged, a welder had to crawl inside and make a weld in an awkward position close to his body.

Any number of things could go wrong to prevent the optimal operation of the plant. Water flow to the wheel was sometimes interrupted by canal leaks or obstructions in the pipe. As such, the operator of the plant had to constantly monitor the canal to ensure its proper flow.

“Small leaks soon became cascades that if unchecked could rip out hundreds of yards of canal bank,” Hall wrote. “When flow was being restored, water had to be slowly ushered into the pipe; if an air bubble were allowed to form the resulting pressure would rupture the pipe.”

Another problem that could occur was sand abrasion resulting from flooding, along with other issues that would result from too much water flow.

“Thunder showers were a double threat; if they happened upstream, they could load the river with silt,” Hall explained. “ If they happened locally, they could send avalanches of rock and water down the canyon-side that would rip out whole sections of canal.”

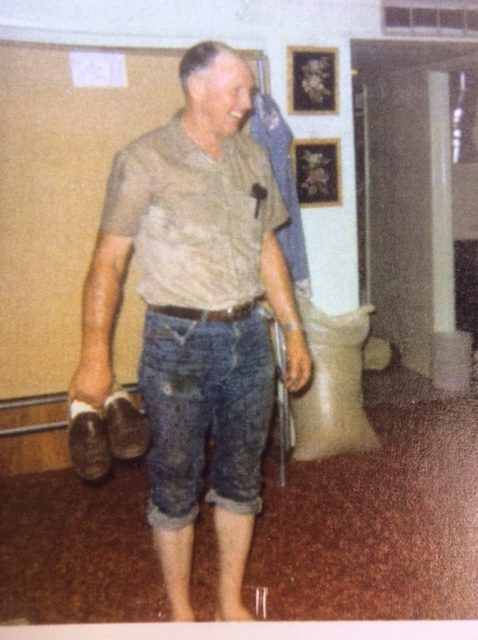

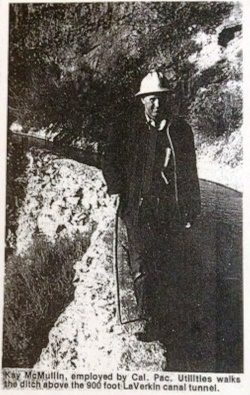

Kay McMullin operated the plant the longest, from 1958 until it closed in 1983. At first, he worked for California-Pacific Utilities, which was later bought out by Utah Power and Light. Ordinarily working alone, McMullin’s constant worry was the flow of the canal as well as the water through the pipe.

McMullin’s daughter, Leandra Skeem, said her father walked the canal every day, sometimes twice a day if there were issues with it.

On some of his walks, however, he had company. She said he made his job family-friendly.

“Often he would take one of us kids with him,” Skeem said. “He didn’t like to take more than that at a time because of the risk of falling.”

Another thing McMullin was afraid of on his walks along the canal were snakes. There was one period where he saw so many snakes he carried a shotgun with him to fend them off and if he didn’t have a shotgun, his walking stick was his weapon of choice against them, Howard noted in his article.

He also picked up some souvenirs in all of his walking, according to Skeem.

“He brought home rattles from snakes quite frequently,” his daughter said. “He loved wildflowers. He very often brought my mother a bouquet of wildflowers he would pick along his way.”

They would also take home figs from a fig tree about half way up its course.

Skeem said her trips up and down the canal with her father are “special memories.”

Unlike the earlier operators, the McMullin family did not live in the plant, and Skeem was happy about that because one thing she remembers about the plant itself was the noise.

“That plant was horrifically noisy,” she said. “You had to be a foot away from a person, look them in the eye and shout at the top of your lungs or they had no idea you (were) there,” she said.

Much like the horses of the Hurricane Canal’s ditch riders on the other side of the gorge, McMullin was well acclimated to walking along the canal bank, which was just over six inches wide in some places. If one lost his balance and fell, on one side he’d get wet, on the other he could fall 10 to 20 feet onto rocky terrain.

In his compilation, Hall told the story of when McMullin walked the bank in eight inches of snow and slipped into the canal’s icy water. Fortunately, he had stashed emergency supplies at intervals along the canal and was able to retrieve some matches, start a fire to warm up and survive the ordeal.

Apparently, the worst part of McMullin’s job was when there were problems or when repairs were needed.

“Every time there was a surge in power, or the power went off, this was automatically a ‘call out’ for him to jump and run to work,” Skeem said. “He had to first go to the plant and check the meters there. If they (weren’t) right, he would start walking up the canal to check for water.”

If there were problems in the canal, he would have to close the headgate near the settling pond near the headwaters of the canal so that repairs could begin. Repairs to the canal were not easy because they couldn’t bring up any modern machinery. Instead, fixing the canal included stacking rocks, filling them with dirt and cementing them using hand tools that could be carried up the canal’s length. It was a long, laborious process. For instance, one crack in the canal that spanned 150 feet took three weeks to fix, Howard noted in his story.

“He dreaded these repairs,” Skeem said. “They were hard work. Everything had to be packed in and out.”

The plant closed suddenly in 1983. After McMullin returned from vacation, he found the Pelton wheel and other machinery ruined and no one knew exactly how it all happened. The two theories of the power plant’s demise are that lightning could have caused a power shut off and the deflector plate may have failed to fall into place to prevent the damage or a disgruntled former employee could have demolished it, Hall wrote.

Rebuilding was deemed economically unfeasible and the machinery and pipe were sold as scrap. McMullin transferred to Delta to finish out his career, after which he returned to Southern Utah, Skeem said. He died in 1996.

Once fenced off and inaccessible, Washington County, which owns the park and administers it through the Red Cliffs Desert Reserve, plans to restore the old power plant and provide interpretive signage to tell its story.

The Wilkinson Dairy

Another old structure hikers will see along the Confluence Trail is an old dairy barn which belonged to the family of Lelwin and Viva Wilkinson. It’s heyday was in the 1950s.

The family moved to Hurricane in 1946 and bought what was called the LaVerkin Creek farm in 1948. They bought milk cows and first milked them at the Hurricane Co-op Dairy and later the Vernon Church Dairy in LaVerkin until they built their own barn in approximately 1951-52. After that, they sold their milk to Anderson Dairy in Las Vegas, which would pick up the milk twice a week, Bruce Wilkinson, Lelwin and Viva’s son, said. At the dairy’s peak, Floyd Wilkinson, their oldest son, said the family had about 40-50 head of cattle.

Since it sold milk to a Nevada company, the dairy had to meet Nevada state health requirements, Floyd Wilkinson explained. Those requirements included having plaster on the walls and specific air flows in certain areas. As such, Floyd Wilkinson said the barn cost more per square foot to build than the family’s home.

Floyd Wilkinson said the family milked the cows twice a day, at 4 a.m. and 4 p.m. When he came of age, he said he was in charge of the morning milking and his father and brother Bruce completed the milking in the afternoon.

The family used a surge milking machine that could milk four head of cattle in about six minutes, Floyd Wilkinson said. The cows were very cooperative, waiting in a holding corral and figuring out themselves which cow would go first, he explained. Some couldn’t wait to unload their “cargo.”

“I guess the milk was tight on their udders,” Floyd Wilkinson remarked.

In a letter submitted for publication in Loren Webb’s book “Milking Time” about dairy farms in Washington County, Viva Wilkinson said that her husband was employed by various agricultural agencies in Washington County until he started teaching debate, speech and drama at Hurricane High School in 1954. The dairy then became his second job.

In addition to the dairy, the family also had a peach orchard and raised other crops such as hay, strawberries, onions and a few others.

The peach trees, however, caused a few problems with the herd with some cows breaking through the fences to get the peaches, reaching as high as they could go, Floyd Wilkinson explained.

Lelwin Wilkinson, who graduated with a bachelor’s degree in agriculture from Utah State University, put together a good “mixture” to plant for grazing on one half of their pasture land, and they grew hay on the other half, Floyd Wilkinson explained.

“My summers were spent cutting, raking, bailing and hauling hay,” Floyd Wilkinson said, noting that he helped other farms from Kanarraville to the south with their hay hauling. “I learned how to work. I learned responsibility.”

Through his hard work, Floyd Wilkinson said he earned enough money to always have a good car “and all the gas I needed.”

After running the dairy for a little while, the family bought additional acreage across LaVerkin Creek known as “The Jungle” because it was overrun by willows. The family went to a lot of work to clear it for planting. Not only was the work of clearing the land difficult, but so was maintaining the miles of ditches on their farm, Bruce Wilkinson noted. Floyd Wilkinson said the family eventually owned 60-70 acres.

Fortunately, though, for the Wilkinsons, water was never a problem. Both Bruce and Floyd said their farm benefited from the runoff water coming off the LaVerkin Bench from above.

This additional land, even though it produced well, created more work that eventually became burdensome for the family. In her letter to Webb, Viva Wilkinson wrote that after a few years, the extra work took its toll on her and her husband’s health, which forced them to lighten their load.

Floyd Wilkinson, who graduated from high school in 1959, said his dad admitted to him that without his oldest son, he couldn’t run the farm efficiently. That same year, as Floyd went away to college, the family sold the farm to Lyman Gubler, and Lelwin Wilkinson went back to school himself to get a master’s degree at Michigan State University.

He would end up teaching biological sciences at a high school and junior high in Las Vegas before retiring in Alamo, Nevada. He eventually did move back to Washington City, where he died in 1999, Floyd Wilkinson said.

Once Lyman Gubler took over the farm, it would never be a dairy operation again, as the family sold their milk cows to Kent Wilson, Floyd Wilkinson said. Gubler, instead, ran beef cattle on the Wilkinson’s old farm for a time.

Visiting Confluence Park

Confluence Park is located in the bottom lands between Hurricane and LaVerkin. While it is between two growing cities with housing developments in view on either side of the highlands up above, hikers still feel like they are away from it all.

Today, Confluence Park is a protected natural area managed by Washington County through the Red Cliffs Desert Reserve office. The county, with the help of the Virgin River Land Preservation Association, acquired the property of three landowners, securing funding from the Fish and Wildlife Service as well grants from other agencies to purchase 344 acres. This saved it from development and preserving it as habitat for wildlife. It also protects its historical structures and provides an ideal place for the enjoyment of county residents.

In the spring of 2020, in an effort to begin restoration of the old hydroelectric plant, the county removed the chain-link, barbed-wire fence that surrounded the old hydroelectric plant and placed a sign at the site announcing its intentions. The sign says that the county will renovate the building, clean up the area around it and add a picnic area, install interpretive signage and allow visitors to walk through to view the old hydroelectric generating equipment. The building’s interior is off limits to visitors until that happens, the sign notes.

“We realize that through the past 10 years, this building has been an irresistible target for vandalism,” the sign explains. “We need everyone to be aware that Washington County is now seriously putting money forward to establish this as an interesting and unique property to be appreciated by many. We sincerely hope that we can count on everyone to help this effort move forward.”

The sign goes on to ask any county resident willing to help with the project to contact the Red Cliffs Desert Reserve office.

Another improvement that will soon be made in Confluence Park is a footbridge across the river to connect the Hurricane and LaVerkin sides. The funding for the bridge is coming from grants, including a $150,000 Utah Outdoor Recreation grant with other grants pending, Confluence Park grant writer Kathleen Nielson said.

The park includes a network of 10 trails, all of which are two miles or less. Along the longest trail, the Confluence Trail, is where hikers will find the buildings previously described. Also along the trail, hikers will find the Virgin Anasazi cave dwelling and a nearly completely intact granary used for a former turkey farm. The trail features many access points to the river, one complete with a rope swing hanging from a large cottonwood tree.

The Confluence Trail can be accessed either from the trailhead on the west side of SR-9 just north of the LaVerkin-Hurricane Bridge. In the last year, this access point has been altered by the construction of The Dwellings, a vacation-rental development. Since the county has a 30-foot easement along the property, the trail still be accessed but there is no dedicated parking for it. One can also descend into the park at the very west end of LaVerkin’s Center Street. Another access point is arrived at by turning off SR-9 before it crosses Ash Creek and into Toquerville to a trailhead parking lot.

For more information, visit the Red Cliffs Desert Reserve’s webpage about Confluence Park, which includes a map of its trails.

Photo gallery follows below.

About the series “Days”

“Days” is a series of stories about people, places, industry and history in and surrounding the region of southwestern Utah.

“I write stories to help residents of southwestern Utah enjoy the region’s history as much as its scenery,” St. George News contributor Reuben Wadsworth said.

To keep up on Wadsworth’s adventures, “like” his author Facebook page or follow his Instagram account.

Wadsworth has also released a book compilation of many of the historical features written about Washington County as well as a second volume containing stories about other places in Southern Utah, Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada.

Read more: See all of the features in the “Days” series

Click on photo to enlarge it, then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

This historic photo shows Kay McMullin just after he had walked the LaVerkin Canal to check for leaks, Hurricane, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Leandra Skeem, St. George News

This historic photo, which appeared in a 1975 "Spectrum" article, shows Kay McMullin walking the LaVerkin Canal, LaVerkin, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Leandra Skeem, St. George News

The south access point to the Confluence Trail is now enveloped by the Dwellings with no dedicated parking, LaVerkin, Utah, Aug. 8, 2020 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The old LaVerkin hydroelectric plant sits by the river, visible from the south Confluence Park trailhead at The Dwellings, LaVerkin, Utah, Aug. 8, 2020 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth

The old LaVerkin hydroelectric plant is approached by the Confluence Trail, LaVerkin, Utah, Aug. 8, 2020 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Recently, Washington County removed the chain-link fence with barbed wire on top that once surrounded the old LaVerkin hydroelectric in preparation for its restoration, LaVerkin, Utah, Aug. 8, 2020 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A sign west of the old LaVerkin hydroelectric plant informs visitors of Washington County's intentions to restore it, LaVerkin, Utah, Aug. 8, 2020 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Unfortunately, the former hydroelectic plant's Pelton Wheel, other interior machinery and walls have been vandalized, LaVerkin, Utah, Aug. 8, 2020 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Unfortunately, the former hydroelectic plant's Pelton Wheel, other interior machinery and walls have been vandalized, LaVerkin, Utah, Aug. 8, 2020 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This sign used to direct hikers to the Confluence Trailhead just north of the LaVerkin-Hurricane Bridge before the construction of The Dwellings, LaVerkin, Utah, Dec. 15. 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The old LaVerkin hydroelectric plant, as seen from the Confluence Trail's descent to near the Virgin River's bank, Confluence Park, LaVerkin, Utah, Dec. 15, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The remains of an old rusty 1930s car that apparently drove off the side of the cliff, lying along the Confluence Trail, Confluence Park, LaVerkin, Utah, Dec. 15, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

View of the old LaVerkin hydroelectric plant seen from the trail's approach to it from the east, Confluence Park, LaVerkin, Utah, Dec. 15, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The old pipe that fed water to turn the hydroelectric plant's Pelton wheel, Confluence Park, LaVerkin, Utah, Dec. 15, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This photo shows the old hydroelectric plant when it was fenced off, Confluence Park, LaVerkin, Utah, Dec. 15, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A peak inside the interior of the old LaVerkin hydroelectric plant, which was once fenced off, Confluence Park, LaVerkin, Utah, Dec. 15, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The view from the west side of the old LaVerkin hydroelectric plant when it was fenced off, Confluence Park, LaVerkin, Utah, Dec. 15, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The old LaVerkin hydroelectric plant in the foreground with River Rock Roasting sitting atop in the background, Confluence Park, LaVerkin, Utah, Dec. 15, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Trees along the Confluence Trail, Confluence Park, LaVerkin, Utah, Dec. 15, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

An old granary used as part of a turkey farm along the Confluence Trail, Confluence Park, LaVerkin, Utah, Dec. 15, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

View of the turkey farm granary from above, Confluence Park, LaVerkin, Utah, Dec. 15, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A Virgin River access point along the trail that boasts a rope swing attached to an old Cottonwood tree, Confluence Park, LaVerkin, Utah, Dec. 15, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

An Anasazi cave dwelling near the intersection of the Confluence and Cactus Cliff trails, Confluence Park, LaVerkin, Utah, Jan. 10, 2019 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

View of the of the old Wilkinson dairy barn and corral from the LaVerkin Center Street trailhead, Confluence Park, LaVerkin, Utah, Jan. 10, 2019 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The afternoon sun sets the old Wilkinson dairy barn and surrounding landscape aglow, Confluence Park, LaVerkin, Utah, Jan. 10, 2019 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews