FEATURE – When one thinks of concentration camps, what usually comes to mind are the Nazi Germany camps of World War II but what many may not realize is that the United States had its own version of concentration camps during that era and one was situated in central Utah.

The camps in Nazi Germany cannot be forgotten: They implemented what was called the Final Solution to the “Jewish problem”; they used gas chambers to eliminate those unfit to work and treated those fit to work worse than the slaves of the antebellum South; they were collectively known for the Holocaust leading to the death of approximately 6 million Jews and others their perpetrators considered undesirable.

While nearly nothing like the Nazi camps and lacking such an evil purpose, a United States version of concentration camps – some top government brass (including President Franklin D. Roosevelt himself) even called them that – did exist. Their aim, however, wasn’t to eliminate people; their aim was to keep a watchful eye on an entire race – those of Japanese ancestry – approximately two-thirds of whom were American citizens. They were known more formally as internment camps or the more euphemistic “relocation centers.”

The Central Utah War Relocation Center was established northeast of Delta, called Topaz after a nearby mountain.

America’s internment camps affected approximately 120,000 people on the West Coast and very few died in the camps. But even though the camps were distinctly different from their German counterparts, to many, what happened in the internment camps cannot be easily excused and swept under the rug. The camps took away residents’ basic civil and constitutional rights in the name of national defense while in reality – particularly in hindsight – they may represent a bad case of war hysteria.

There were rumors of sabotage with practically no distinction made between Japanese nationals and Japanese immigrants living in the U.S. with their citizen children.

“Ironically – though this mass incarceration was provoked by accusations of disloyalty – not a single Japanese American was prosecuted or convicted for any instance of espionage toward the United States,” the Topaz Museum brochure states.

Minister Truman B. Douglass wrote in a 1944 pamphlet:

This did not occur in a foreign country under tyrannical dictatorship, 70,000 American Refugees Made in USA. …

It happened in America under the flag which stands for ‘liberty and justice for all.’

The Executive Order

In the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, on Feb. 19, 1942, under pressure from within and without his administration, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the relocation of Americans of Japanese ancestry to 10 camps across the Western United States to ensure they didn’t do anything to aid the Japanese government as they feared might happen.

Just as the U.S. Constitution does not include the word “slavery,” the words “Japanese” or “Japan” were not included in the order, but everyone knew what people the edict referred to.

Without any hearings or trials, these Japanese-Americans were given short notice – some only days – to prepare to leave the life they had known for so long for the unknown. Most did not even know where they were going as they boarded the trains to leave. They could only take what they could carry, meaning that many of them had to sell high-value possessions, such as homes and cars, at fire-sale prices.

Partly due to the loyalty infused in their culture, most didn’t put up a fuss and left without any strife, staying in the camps with patient resignation waiting for the day they would be free to build their own lives where they wanted to again.

Topaz daily life

Topaz opened on Sept. 11, 1942 upon the arrival of trains carrying 500 internees and 50 military guards after long trips in which they were packed in rail cars like sardines. Most came from the San Francisco area and prior to their arrival at Topaz were incarcerated at the Tanforan Race Track in San Bruno, Calif., forced to live in horse stalls until Topaz was completed.

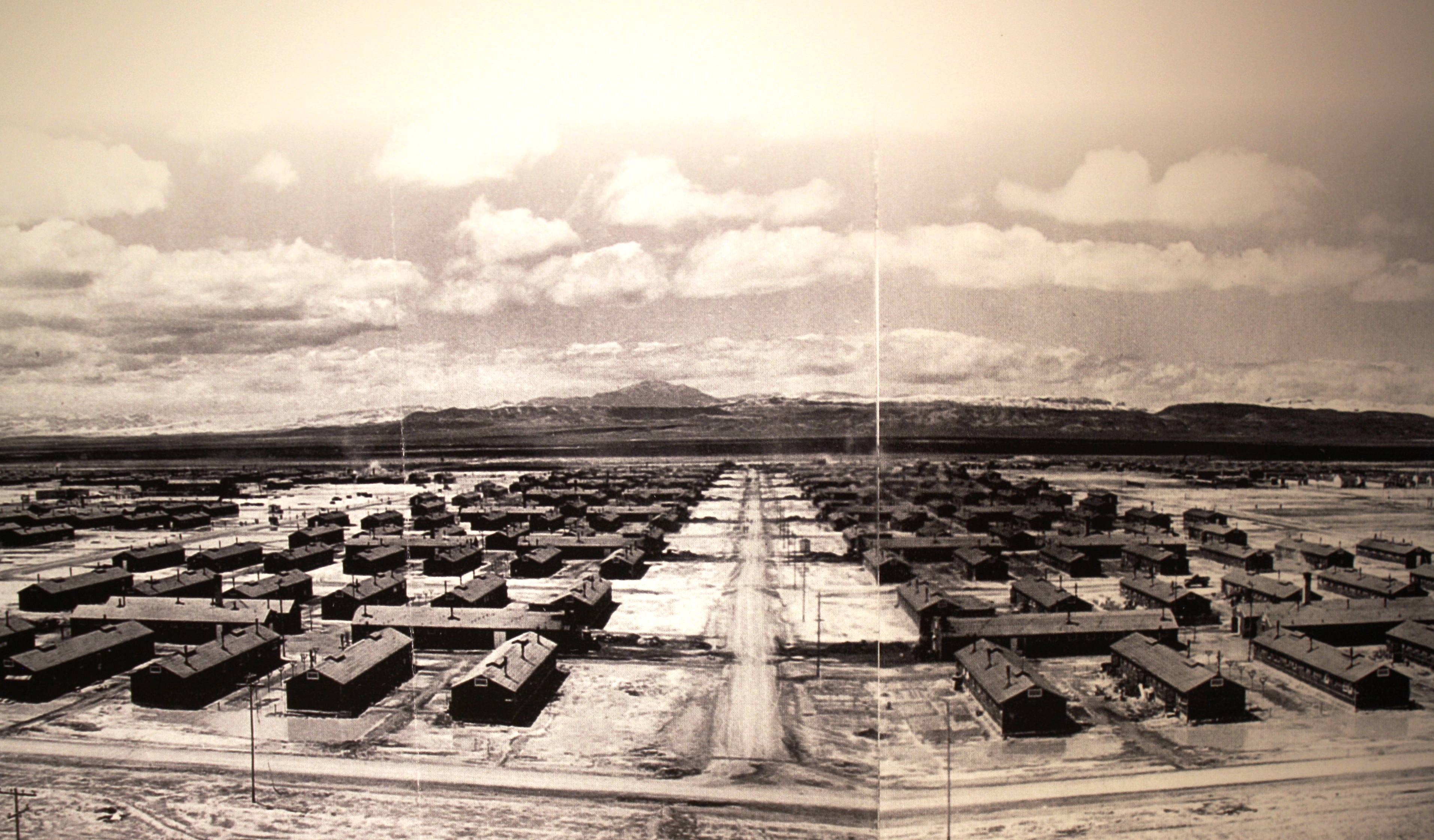

Topaz housed 11,212 residents during its short stint and its peak population was about 8,100. Topaz was its own enclosed city – the fifth largest in the state at the time – during its just more than three-years existence.

When the first batch of people arrived, not everything was finished.

“Once at the Topaz location, some internees were hired to finish building their own barracks, put up the barbed wire fence, and complete other structures at the site,” the museum’s history page notes.

The camp included 42 blocks; the first few were the administration buildings, warehouses and government workers housing with the remaining blocks housing residents. Each block included 12 apartment buildings, a recreation hall, men’s and women’s latrines and a mess hall. Each building was sectioned off into six apartments of different sizes to accommodate families.

Families lived in one-room barrack-style housing that “were little more than pine planks covered with tar paper on the outside and sheet rock on the inside,” one museum interpretive panel notes. In each room were four army cots without mattresses, a coal stove, a light bulb, and two army blankets per person. Many internees built additional furniture from scrap wood.

The crowded spaces ranged from 20 feet by 14 feet for two people to 20 feet by 26 feet for a family of six. The barracks had no running water or insulation and during windstorms dust found its way in through the doors, walls and windows even though rags and wet newspapers were stuffed in the cracks.

Families tried to make the best of the situation. Adults had jobs that paid them a pittance (wages ranged from $12-$19 a month) but soldiered on. Children went to school at one of two elementary schools or the junior-senior high school. Some residents even cultivated their own gardens.

Even in such conditions, 136 couples were married in Topaz; their courtships consisted of more mundane things such as sharing tomato soup around a potbellied stove or watching a movie in the recreation hall. They had to travel to Fillmore, the county seat 54 miles away, just to get a marriage license.

Anna Towata, who was one of those Topaz brides, wrote that she cried on her first anniversary because all it consisted of was going to a mess hall for dinner and then going to another mess hall for a movie, according to one of the museum’s interpretive panels.

“This is no first anniversary,” she complained to her husband, who responded, “Don’t worry, there’ll be other anniversaries.” And there were — 49 of them.

Topaz youth went to school just like anyone else, but it was more difficult for them to be motivated under their circumstances. A War Relocation Authority report about Topaz in 1944 even noted that Topaz students showed an attitude of resignation and apathy toward the future, a museum interpretive panel notes, but the students’ teachers, both Japanese and American, encouraged them to never give up.

“I never ceased to have a lump in my throat when classes recited the Pledge of Allegiance, especially the phrase ‘liberty and justice for all,’” said Eleanor Gerard Sekerak, who was a student at Topaz.

Once in a while, however, Topaz students did have something to be proud of and to keep them going, such as when the Topaz football team defeated Millard High School Nov. 11, 1943.

Art was an escape for Topaz internees, both youth and adults alike. They sculpted wood into smooth shapes or gathered shells to make delicate jewelry and even dolls. Others expressed themselves through traditional dance, flower arranging, music and poetry.

Internees published a daily newspaper called The Topaz Times and issues of a literary arts magazine called TREK and a similar one called All Aboard.

“On the surface, the paintings, drawings and artwork from Japanese Americans at Topaz may look pleasant,” a museum interpretive panel says, but looking closer at them, they feature guard towers and barbed wire and serve as a sort-of diary. “The art produced at Topaz is some of the most powerful to come out of the WRA camps.”

In early 1943, the War Department and the WRA required everyone in internment camps that was 17 or older to take a loyalty questionnaire.

“The questions, focusing on their religion, language and club memberships, caught Japanese Americans off guard,” a museum interpretive panel states. “Some questions were confusing, others seemed like entrapment.”

Anyone deemed disloyal – and there were 1,400 of them at Topaz – was sent to a high security camp at Tule Lake in northern California. For some, saying “no” to certain questions on the form wasn’t a matter of loyalty, but one of protest.

The questionnaire did lead to internees around the nation being drafted into or volunteering for the U.S. Army. The irony is these former internees were fighting for a country that stood for freedom but still incarcerated their families.

These young Japanese Americans from the internment camps joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team in Europe, the museum brochure states, which became the U.S. Army’s most highly decorated unit for its size and duration of service.

One of the most unfortunate incidents to occur at Topaz was the shooting death of 63-year-old James Wakasa by one of the Topaz guards on April 11, 1943. The guard gave no warning shot and claimed Wakasa was trying to escape. The death caused quite a stir with internees fearing they would be targeted by “Jap-hating guards” and Japanese leaders demanding they be part of the investigation. The guard was tried but let off; after the shooting, however, policies relaxed and soldiers in the guard tower were removed during daylight hours.

After Topaz closed in October 1945, people from all over Utah bought and removed its buildings for use as houses and farm buildings. Half a barrack sold for $250. For instance, Delta farmer Eldro Jeffery purchased half a barrack that once served as a Boy Scout meeting hall; his family donated it to the Great Basin Museum in 1991 and the Topaz Museum Board later restored it to its 1943 appearance as an exhibit for the museum.

The apology

A presidential commission investigated the incarceration of Japanese Americans in the early 1980s. At the time of incarceration, the action was implemented without a dissenting vote, but looking back, hindsight is truly 20/20.

“The promulgation of Executive Order 9066 was not justified by military necessity, and the decisions which followed from it – detention, ending detention and ending exclusion — were not driven by analysis of military conditions,” the presidential commission’s report stated. “The broad historical causes which shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”

For years after the camps were closed, Japanese-American groups sought an apology and redress from the government. That finally came when Congress passed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which acknowledged it had violated internees’ basic civil liberties and constitutional rights. The act authorized payments of $20,000 to each living camp survivor, more than 82,000 of them. Unfortunately, the apology came too late for nearly 40,000.

“A monetary sum and words alone cannot restore lost years or erase painful memories; neither can they fully convey our Nation’s resolve to rectify injustice and to uphold the rights of individuals,” read President George Bush’s apology letter that accompanied the redress checks.

“We can never fully right the wrongs of the past,” Bush’s letter continued. “But we can take a clear stand for justice and recognize that serious injustices were done to Japanese Americans during World War II. In enacting a law calling for restitution and offering a sincere apology, your fellow Americans have, in a very real sense, renewed their traditional commitment to the ideals of freedom, equality, and justice.”

That 1988 legislation also made it okay to talk about the internment camps and their story began to find its way into the country’s historical narrative as well as become part of the curriculum for U.S. history courses.

The museum

In 1976, Japanese American Citizen League chapters from Salt Lake City erected a monument near the site of the former Topaz camp.

The Topaz Museum Board was established in 1997 as a nonprofit organization with the avowed mission to preserve the history of Topaz Camp. In 1999, the board began purchasing land of the former Topaz camp site and to date owns 626 acres of its original 640 acres.

The National Park Service named the site a national historic landmark in 2007 and by 2011 the board possessed 87 paintings done at the Topaz Art School.

The board received park service Japanese American Confinement Sites grants and raised additional funds to construct the museum, which was finished in 2014. It opened in 2015, first displaying the Topaz art.

The grand opening of the museum exhibits recounting the history of the Topaz Internment Camp followed July 7-8, 2017.

Visiting Topaz

The Topaz Museum is located at 55 W. Main St., Delta, next door to the Great Basin Museum. It is an approximate 2.75-hour drive from St. George via Interstate 15, state Route 100 and U.S. Highway 50.

At the museum, visitors can watch two short videos, one containing excerpts of home videos taken by Topaz internee Dave Tatsuno and another about the camp’s history. The informative museum displays depict daily life in the camps with poignant pictures and artifacts, show a re-creation of one of the barrack living quarters and the restored recreation hall in the back of the museum.

The museum, open Mondays through Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., provides visitors a copy of a map with directions to the actual Topaz site as well as an information sheet detailing where some of the former barracks currently reside in Delta.

Since the camp’s buildings were sold and carted off to other places, the site itself contains only a few remnants of the actual camp, including building foundations, a coal chute and a few other odds and ends. An Eagle Scout project installed signs showing where former camp buildings once stood as well as markers denoting the location of each numbered block.

Even though there isn’t much there anymore, visiting the actual site is a must for visitors – an eye-opening reminder of what conditions were like for these unfortunate people who left real life behind for a manufactured life in Utah’s barren desert.

It also is a reminder that a nation built on freedom should never curtail its citizens’ basic human rights in such a manner again.

For more information about Topaz, visit the museum’s website.

Photo gallery follows below.

About the series “Days”

“Days” is a series of stories about people and places, industry and history in and surrounding the region of southwestern Utah.

“I write stories to help residents of southwestern Utah enjoy the region’s history as much as its scenery,” St. George News contributor Reuben Wadsworth said.

For previews on Days Series stories, insights on local history and information on upcoming historical presentations, please “like” Wadsworth’s author Facebook page.

Wadsworth has also released a book compilation of many of the historical features written about Washington County as well as a second volume containing stories about other places in Southern Utah, Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada.

Read more: See all of the features in the “Days” series

Click on a photo then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

The name "Topaz" fashioned in barbed wire near the flag pole at the former Topaz Internment Camp, a symbol and reminder of the injustices that took place there, Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The marker and flag pole at the corner of the former Topaz Internment Camp site near Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This photo of a historic photo on display at the Topaz Museum shows new arrivals coming to the Topaz Internment Camp near Delta, Utah in 1942, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This photo of a historic photo on display at the Topaz Museum shows new arrivals coming to the Topaz Internment Camp near Delta, Utah in 1942, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This photo of a historic photo on display at the Topaz Museum shows new arrivals coming to the Topaz Internment Camp near Delta, Utah in 1942, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This photo of a historic photo on display at the Topaz Museum shows residents of the Topaz Internment Camp harvesting crops on a farm near Delta, Utah between 1942-1945, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This photo of a historic photo on display at the Topaz Museum shows residents of the Topaz Internment Camp near Delta, Utah gathering between 1942-1945, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This photo of a historic photo on display at the Topaz Museum shows the sunset at the Topaz Internment Camp near Delta, Utah between 1942-1945, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This photo of a historic photo on display at the Topaz Museum shows the the skyline of the Topaz Internment Camp between 1942-1945. Near Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This photo of a historic photo on display at the Topaz Museum shows the the skyline of the Topaz Internment Camp near Delta, Utah between 1942-1945, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This photo of a historic photo on display at the Topaz Museum shows Topaz high school students at their senior banquet in May, 1945, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This photo of a historic image on display at the Topaz Museum shows a cartoon featured in an issue of the Topaz Internment Camp newspaper, the Topaz Times, between 1942-1945, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This photo of a historic photo on display at the Topaz Museum shows residents of the Topaz Internment Camp near Delta, Utah saying goodbye to a group leaving the camp between 1942-1945, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This photo of a historic photo on display at the Topaz Museum shows the gate at the Topaz Internment Camp near Delta, Utah being ceremoniously locked when the camp closed on October 31, 1945, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The exterior of the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A photo of an interview with Topaz Internment Camp resident Dave Tatsuno that is part of a video compilation of home movie footage he shot while in the camp that visitors are invited to watch after they enter the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Floral arrangements fashioned of shells made by Topaz residents on display at the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Panel of an enlarged photo of a family headed to Topaz that first greets visitors as the walk into the main part of the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The first hall of museum displays visitors see at Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Display about future internment camp residents' need to sell the belongings they couldn't carry before leaving to the internment camps at the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A display about Topaz's newspaper, the Topaz Times, at the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Photo of a painting of a dust storm Topaz residents had to endure at the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A re-creation of what housing was like for Japanese-American families living at the Topaz Internment Camp at the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A re-creation of what housing was like for Japanese-American families living at the Topaz Internment Camp at the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A display showing furniture Topaz residents made from scrap wood to supplement the meager furnishings given to them during their stay at the Topaz Internment Camp, A re-creation of what housing was like for Japanese-American families living at the Topaz Internment Camp,Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A display about Topaz's high school, including a letterman jacket at the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A display about marriage and health in the Topaz Internment Camp at the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The inside of the restored recreation hall behind the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The sign that greets visitors to the former site of the Topaz Internment Camp in Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Markers, which were part of an eagle project, let visitors know what once stood at the Topaz Internment Camp. Delta, Utah, June 11, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2018, all rights reserved.

Great article. Makes me want to visit this museum.

Also confirms my opinion that FDR was not the hero so many would like to believe him to be.

FDR did what needed to be done.

JPD…….absolutely !

Not in this instance.

Many things about America’s reaction to WWII were terrific. Everybody pulling together for rationing, recycling. Bonafide stars like Jimmy Stewart heading off to serve in the military. Women stepping into roles they had previously been excluded from and performing magnificently.

But others leave you shaking your head. Like American Citizens of Japanese ancestry being deprived of their legal rights and placed in concentration camps. Like German POW’s held in the American South being allowed to freely roam towns and patronize restaurants and businesses while black American servicemen were denied the same freedoms.

FDR (like all human beings) was a mixed bag. He did some good—maybe even heroic—things, and some terrible things. This was one of the terrible things. Throughout the internment process, the government caught no spies in the camps; we have zero evidence they increased national security one iota. For this lack of results, thousands of citizens were deprived of their constitutional rights. It’s disgraceful. Reagan apologized. Bush paid reparations. Now it’s up to all of us to make sure it never happens again.

On to the article itself…very nicely done Mr. Wadswoth. I’ve done a fair bit of reasearch on the camps in the past but still learned new details from this piece.

Great article Mr.Wadsworth! This reminds me of a book i read in intermediate school called “Under the Blood red Sun”.

I hope we cover this in class. I feel like the causation of this event is relatable to many peoples current sentiment and rationale. I think it is very important to remember events like this in order to learn from our mistakes so we don’t repeat them and to come up with solutions instead of letting fear guide us.

jorge w. -do i get extra credit for this? lol jk