ST. GEORGE – A jury announced Friday morning it had reached a verdict in the case of St. George businessman Jeremy Johnson, accountant Scott Leavitt at Johnson’s I Works online marketing company and former general manager Ryan Riddle following a six-week trial that began last month in Salt Lake City’s federal court.

Nearly five years after the first charge was filed, a jury of nine men and three women, in deliberations since Monday, reached their unanimous verdict Friday on the 86 charges, centered on allegations of bank fraud, faced by Johnson and Leavitt and 56 charges faced by Riddle.

The jury found Johnson guilty on eight counts of making false statements to a bank.

Johnson was found not guilty on 78 charges that included one count of conspiracy, two counts of making false statements to a bank, 13 counts of bank fraud, 23 counts of wire fraud, nine counts of participating in a fraudulent banking activities, two counts of conspiracy to commit money laundering and 30 counts of money laundering.

Riddle was found guilty on six counts of making false statements to a bank.

Riddle was found not guilty on 50 charges that include one count of conspiracy, 13 counts of bank fraud, 16 counts of wire fraud, four counts of participating in a fraudulent banking activities, two counts of conspiracy to commit money laundering and 14 counts of money laundering.

The jury found Leavitt not guilty on all counts.

Johnson and Riddle are scheduled to be sentenced on June 20.

Johnson and Riddle each acted as their own attorney during the trial, while defense attorney Marcus Mumford represented Leavitt.

The three men went on trial last month without having access to emails, information and possible evidence on an I Works company server after U.S. Magistrate Judge Paul Warner said in a pretrial hearing that all efforts had failed to recover emails missing from the server.

Chargebacks

The codefendants’ troubles began in 2009 when Johnson’s I Works company – which sold information on moneymaking opportunities such as how to apply for government grants for personal expenses and how to earn income from Google AdWords – began experiencing a high rate of consumers demanding refunds on their credit cards, actions known as chargebacks.

The chargebacks were enough to get I Works placed on a warning list, allegedly prompting Johnson, Leavitt, Riddle and others to set up a series of “shell companies” using the names of employees, friends and family in order to apply for and open new accounts at Wells Fargo Bank.

On the second day of trial, according to court documents, Martin Elliott, global head of brand protection for Visa USA, testified that I Works-related companies had record high numbers of chargebacks which he said prompted hundreds of thousands of dollars of fees assessed to the banks with an “extremely negative impact” to the banks, Visa and credit-card holders.

Following Elliott’s testimony, Johnson told U.S. District Judge David Nuffer, who presided over the trial, that some of the accounts mentioned by Elliott weren’t those of I Works, but that he would need access to an I Works company computer server to prove that.

Johnson said a 2009 recording of a meeting with Elliott, which he claims was made at the suggestion of Visa, directly contradicts some of Elliott’s testimony.

The defendants alleged they were acting on advice from Wells Fargo decision makers and a credit card processor that worked for the bank, that there was no intent to defraud the bank and that there was no attempt made to conceal Johnson’s association with the new corporations.

Shannon Walker, an employee of the Town & Country Bank of St. George, testified during the trial that she had worked with Leavitt in setting up bank accounts for the companies created by I Works. Walker told the court she saw nothing improper in the paperwork used to set up the accounts and that she didn’t have a sense anyone was trying to conceal that they were associated with I Works.

Mumford argued there was no fraud because the banks, brokers and the credit card issuers knew what I Works was doing and that Johnson had put more than $5.5 million in to cover any fines, penalties and expenses on the accounts.

Arrest and missing evidence

Johnson pressed the Utah court numerous times to order the government to give him access to another hard drive known as the “yellow” server, stating the copy provided to the defense did not work, according to court documents, while the government’s copy could be perused for possible evidence, but Warner and Nuffer rebuffed those requests.

The defendants contended their emails from a critical period within the indictment are missing from a company server that had been seized after the Federal Trade Commission sued Johnson, I Works and others in in federal court in Nevada in December 2010.

During that time, the FTC persuaded a judge to seize all of Johnson’s assets and those of his companies and then contacted the U.S. attorney’s office in Utah about possible criminal charges. Prosecutors in Utah charged Johnson with one count of mail fraud and arrested him at the Phoenix airport.

Johnson spent 96 days in jail before being allowed to post $2.8 million in bail collateralized by properties put up by his family and friends. Johnson then began a news and social media campaign to denounce what he considered government abuses by federal regulators and prosecutors. The effort led the court to place Johnson under a gag order prohibiting him from talking about the case.

In 2012, Johnson said lead prosecutor Brent Ward began threatening him with indictments against family, friends and employees if he did not accept a deal in which he would plead guilty to bank fraud and money laundering and receive an 11-year prison sentence.

One of Utah’s biggest political scandals

The plea deal later fell apart in 2013 and the case, initiated with a single fraud charge, ballooned to an 86-count indictment after Johnson insisted that, in exchange for his guilty plea, Ward had promised not to go after a list of people Johnson had submitted including his family, friends, I Works employees and former Attorney General John Swallow.

Johnson is a key figure in the public corruption cases against Swallow and former Attorney General Mark Shurtleff in one of Utah’s biggest political scandals, sparked by Johnson’s January 2013 revelations that Swallow had played a role in an effort to bribe then-U.S. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nevada, on Johnson’s behalf.

Following an investigation, Swallow and Shurtleff are facing criminal charges including charges related to an alleged pay-to-play scheme in the attorney general’s office. Johnson requested to call the two as witnesses in his trial because he said they had declared his business legitimate. However, Nuffer prohibited Johnson from mentioning Swallow or Shurtleff during the trial.

Motions to dismiss

The defense filed several motions seeking to get the case dismissed for a variety of reasons. Among the motions were allegations of prosecutorial misconduct, missing evidence and complaints the government was too slow to bring the case to trial.

A motion to dismiss the case was also filed because the government had seized thousands of private emails between Johnson and his attorneys, according to court documents. Prosecutors had argued that while they had possession of the emails, the prosecution team had not read them or made use of them for their case.

Nuffer denied all of the defendants’ motions to dismiss the case.

Request for gag order clarification

Johnson also filed a motion for clarification on the court’s gag order Tuesday due to an email Johnson had received from Assistant U.S. Attorney Michael Kennedy after Johnson filed a motion to dismiss based on prosecutorial misconduct.

With no further explanation, Kennedy’s email to Johnson read: “Your pleading is little more than an undisguised effort to violate the Court’s gag order. We are treating it as such.”

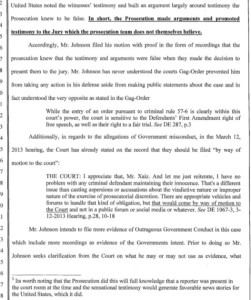

In the motion, Johnson contends that the prosecution made arguments and promoted testimony to the jury which the prosecution does not believe to be true. Accordingly, Johnson filed his motion with evidence in the form of recordings to show that the prosecution knew the testimony and arguments were false when they made the decision to present them to the jury.

Johnson said he was unaware that the court’s gag order prevented him from defending himself in court.

Nuffer orders restriction on jurors

On Wednesday, Nuffer proposed restrictions on how jurors can be contacted, what jurors can say during interviews with counsel and the public after a verdict has been rendered and that the court may even “forbid such interviews” altogether. Another of Nuffer’s restrictions would prohibit jurors from disclosing “evidence of alleged improprieties in the jury’s deliberations.”

Mumford rebutted that the restriction is a “particularly onerous prior restraint on free speech, which places the Court as a continuing gate-keeper for any and all contact with jurors,” according to court documents.

Mumford added in his objection:

We know of no authority that allows the Court to be so involved in the post-trial affairs of jurors, when the threat to justice is substantially lower. In fact, the Fifth Circuit specifically condemned the practice of requiring a showing of “good cause” in order to speak with jurors.

“A court may not impose a restraint that sweeps so broadly and then require those who would speak freely to justify special treatment by carrying the burden of showing good cause. The first amendment right to gather news is ‘good cause’ enough.”

Despite objections, Nuffer issued an order regarding juror contact Thursday.

Among other restrictions, the order prohibits a juror from disclosing any information about the votes of another juror and the opinions expressed by jurors in deliberations, or evidence of alleged improprieties in the jury’s deliberation. The order permits disclosure of whether extraneous information or outside influence was improperly brought to the jurors outside the courtroom and whether a mistake was made in entering the verdict on the verdict form.

The order requires anyone wishing to contact a juror to send the court a statement about why the person wants to contact a juror, and the court would then decide whether to pass along the request.

Nuffer said he wanted to shield jurors from prying questions, increase “the certainty and finality of the jury’s verdict” and reduce the number of “merit-less post-trial motions.”

Court document resources

- Jury Verdict

- Motion to dismiss (or for mistrial) for prosecutorial misconduct during closing argument

- Motion to clarify gag-order

- Notice of Proposed Instruction and Order on Jurors

- Mumford Objection to Court’s Proposed Juror Contact Order

- Johnson 1394 Johnson Objection to Proposed Juror Contact Order

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2016, all rights reserved.