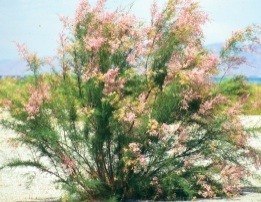

WASHINGTON COUNTY – For years, cities in Washington County have been trying to remove saltcedar, better known as tamarisk, a non-native, invasive species that is a threat to native flora and fauna as well as a flood and fire risk. A multi-agency effort to gain control over the proliferation of the tree is seeing progress.

Steve Meismer, local coordinator of the Virgin River Program, one of the organizations assisting in tamarisk removal and the restoration of native habitat, said the tamarisk is “kind of like the cockroach of the plant world” because it is “very good at surviving.”

The reason tamarisks survive despite restoration efforts is they extend a very long taproot, and can still thrive quite a distance from water, Meismer said. They create an environment to help themselves by dropping leaves that build up with salt, “choking out” riparian habitat, Christian Edwards, a wildlife biologist with the Hurricane office of the Utah DWR, said. Besides the salt, the tamarisk and its debris make the area underneath hotter than in native cottonwoods and willows, Meismer said. Even after being cut out, sometimes the tamarisks have come right back.

To control the saltcedar, the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources has used biocontrol, releasing tamarisk beetles in 2006 that specifically feed on the tamarisk.

“As far as we can tell,” Edwards said, “the beetles are still doing their job.”

In addition, the agency has teamed up with other entities to control the tamarisk population “mechanically,” by going in with chainsaws to cut them out, Edwards said. One example Edwards pointed out was the Santa Clara Fire Department, which has helped cut out tamarisks, put their branches in piles, burn them, treat the removal area with the herbicide Garlon to minimize their return, and replant the area with native Coyote Willow. Funding for the removal has come from the local municipalities, the DWR, the Walton Family Foundation and other sources.

Santa Clara Fire Chief Dan Nelson said tamarisk removal is an ongoing project which his department assists in as needed.

“It’s a pain,” he said. “It’s a dirty, hard job.”

Since tamarisk wood is so hard, Nelson said it has damaged some chainsaw chains.

St. George City Engineer Jay Sandberg said the city has been actively removing tamarisk for many years. When tamarisks are removed, groundwater starts to come up, he said, improving the river environment.

Even with removal and restoration efforts, there has been tamarisk regrowth, Edwards said.

One of the major aims of the removal is to restore habitat for the Southwestern Willow Flycatcher, a native bird on the endangered species list, Edwards said. The DWR has monitored the bird extensively the last six years, he said, and the birds seem to like nesting in tamarisk because the trees provide good cover for their nests in the debris. Meismer said the structure of the branches aids the bird and the tamarisks’ debris underneath helps camouflage flycatcher nests.

When the beetles were released, Edwards said the flycatchers started shifting to nesting in willows. The restoration goal is to remove approximately 70 percent of the tamarisk and leave 30 percent, to find a balance for the flycatchers and encourage them to embrace the native habitat. Meismer said they’re trying to allow that combination without the tamarisks taking over. Edwards said the population has been steady the last five years and that he hopes the restoration efforts will increase the population.

Over 100 acres of willows and cottonwoods have been restored so far in Meismer’s estimation. It doesn’t sound like much, but for an area along the riverbank, it is significant, he explained.

The removal of the tamarisk does not fall squarely on one agency or entity. While the Utah DWR has been the driving force in tamarisk removal in Washington County, Santa Clara, St. George and Washington cities, the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Virgin River Program and private landowners and others have all had a hand in helping restore the riparian habitat along the river, Edwards said.

“It’s a group effort to remove them,” Meismer said, poining out he feels the restoration effort is going well. “Everyone is doing their part.”

Other than choking out habitat of native plants and animals, the tamarisk poses a fire hazard. For instance, some tamarisks were involved in the June 1 fire at Seegmiller Marsh. Meismer said tamarisk burns better when it’s green than when it’s brown and that the trees contain oils that create huge flames.

“It’s almost like lighting a bucket of diesel fuel on fire,” he explained.

“When it burns, it’s super hot,” Nelson said, explaining that homes near tamarisk run a potential risk of catching fire. Tamarisks’ dry, dense “litter” underneath them helps to spread fire growth, Nelson said.

Meismer said there have been a number of tamarisk-involved fires over the years that have been very dangerous.

Cottonwood and willow trees help reduce fire risk, Meismer said, and create a better environment for both wildlife and people.

Tamarisks also pose a flood risk, Meismer said. They are a “very woody” species and are inflexible, whereas willows will bend. For instance, during the 2005 flood, Meismer said the tamarisks’ stiffness created debris dams that augmented the flood damage. Sandberg said tamarisks lead to more buildup of settlement, which produces a focused channel with high-velocity torrents. Willows are better at letting debris pass, Meismer said, which leads to a more controlled environment that lessens damage.

The floods of 2005 and 2010 aided the habitat restoration, Meismer said, especially the 2010 flood, in whose aftermath more native vegetation started to return due in part because of restoration efforts.

Meismer thinks it’s not possible to completely eradicate the tamarisk, but it will be possible to keep it manageable.

“I think, over time, we can keep it under control,” he said.

Related posts

- Firefighters spend 2.5 hours extinguishing 50-60 foot flames

- Environmental Interests Collide Along Virgin River – 2011

- News short: Brush fire at 2450 East Park

- UDOT, Dixie National Forest mitigate bug-kill trees; traffic impacts

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2014, all rights reserved.

Always makes me wonder, who was the original idiot who brought it here?